“Even in the president’s heartlands, in Eastern Ukraine, protesters have come out in strong support of ‘Euromaidan’,” two British academics argued last week on the Washington Post’s political science blog The Monkey Cage, and they drew a far-reaching conclusion: “In effect, Russophones and Ukrainophones, the East and West of the country, young and old, ethnic Russians and Ukrainians [have] united against – what they increasingly regard as – the illegitimate rule of the president and his party”.

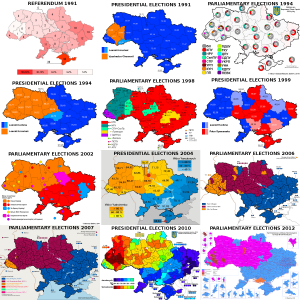

A similar note was struck in a slideshare that’s circulating on Facebook, called What is really happening in Ukraine, which has been viewed over 650.000 times. Citing “massive protests” arising in the East and the South on January 26, the creators chide the Western press for a tendency to continue portraying the protests “in cold war terms,” as “fundamentally based on ‘ethnic/language’ splitting in Ukraine”.

Map of the situation in Ukraine, 26 January 2014, Sergii Gorbachov

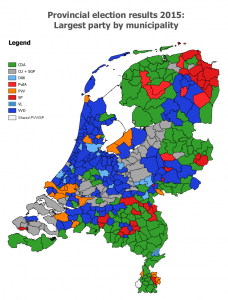

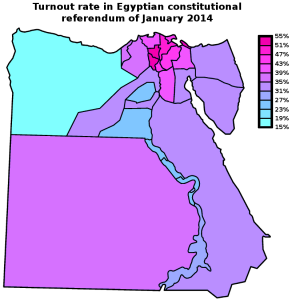

Both arguments came with maps. The Monkey Cage contributors, Kataryna Wolczuk and Roman Wolczuk, presented a map from the Centre for Eastern Studies in Warsaw, which colours most of the country orange (“occupied state administration buildings”) or brown (“mass protests”). The slideshare used three of Sergii Gorbachov’s detailed maps, presenting the situation on January 25-27. On his map from January 26, 21:00, just two of the country’s provinces remained Yanukovych-blue: Donetsk and the Crimea. The rest of the country was in the grip of the revolution: local state administrations were “occupied by [the] people” or the object of “attempted seizures” or “mass protests”.

Map of the situation in Ukraine, 29 January 2014, Centre for Eastern Studies

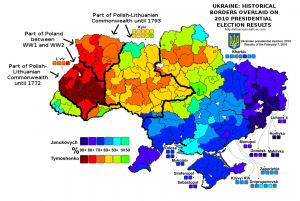

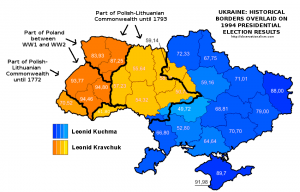

Those maps look very different from the one posted by Max Fischer in the Washington Post just a couple of days earlier, under the title “This is the one map you need to understand Ukraine’s crisis”. Fischer’s map of the regional divide running down the centre of Ukraine between the protesting North and West of the country and the non-protesting South and East neatly overlapped with those of various post-independence election results — and moreover, as I wrote and mapped out last week, with ancient and more recent historical borders as well. So did something fundamentally change, in the last two weeks?

Kataryna Wolczuk and Roman Wolczuk seem to believe so, when they go beyond describing the protests in the South and East as “unprecedented and until recently inconceivable” to describe “the East and West of the country” uniting against Yanukovych. The slideshare authors obviously also believe that analyses that still focus on ethnic/language divides are out of touch with the changing environment.

There are two questions about this argument: To what extent were they right, concerning the developments as they unfolded in the last days of January? And to what extent do any such changes last today?

Protesters in the East: How much of a force?

Poland’s Centre for Eastern Studies, which created the map used in the Monkey Cage blog post, summarized the state of the Ukrainian protests on January 29 in a detailed briefing, covering events across the country. When it came to developments in the South and East, it reported that “demonstrations numbering several thousand and blockades of offices also took place in Dnepropetrovsk, Zaporozhye, Odessa, Cherkassy and Lugansk.”

Cities of Ukraine (Wikimedia)

By then the Centre had already published more detailed write-ups of ongoing events in the previous few days. Its briefing of the 27th cited “massive numbers of participants” in “protests in the largest cities of southern and eastern Ukraine”, which “reached unprecedented proportions”. Detailing the specifics, however, the briefing reported that “several thousand people” took part in an anti-government demonstration in Dnipropetrovsk, a “four-thousand-strong rally” was held in Sumy, a “demonstration of several hundred people” was dispersed in Zaporizhia, “2–3 thousand people” took to the streets in Odessa, “more than one thousand” people demonstrated in Kirovohrad, and so on. Reuters reported “up to 5,000 anti-government protesters” picketing the regional government headquarters in Zaporizhia. The Centre for Eastern Studies’ briefing from a day later added a few details: “a one-thousand strong demonstration” was held in Luhansk, “which may be viewed as another sign of a civil ‘awakening’ of people in eastern Ukraine”; but meanwhile, in Kharkiv, Luhansk, Dnipropetrovsk and Zaporizhia “attempts at occupying administration buildings have been effectively and brutally countered by the police and groups of “titushky”‘.

Even if only a few thousand people took part in those various protests, that may indeed have been unprecedented; after all, in Luhansk for example, Yanukovych received over 80% of the vote in the last presidential elections. The local, Yanukovych-friendly administrations and oligarchs usually keep these cities on a tight reign. But does “several thousand” really equate with “massive,” let alone indicating that the East and the West are finally uniting against the current government? Kharkiv, Dnipropetrovsk and Odessa have a million inhabitants each; Zaporizhia has over 800,000. The same Reuters story reporting on the protest in Zaporizhia also interviewed an opposition journalist admitting that the local protests only attracted the educated middle class: “Unfortunately, Euromaidan’s appeal is very limited here”.

Not all these places are the same either. Sumy and Kirovohrad went for Tymoshenko over Yanukovych in the last elections, so it isn’t all that surprising that opposition protests would break out there. In fact, for two cities with 250,000-300,000 inhabitants which voted for Tymoshenko, a few thousand protesters doesn’t immediately impress, although Sumy protesters did occupy the city’s council building. The size of protests is also sometimes overstated – by both sides, for different reasons. A reporter from the Putin-critical Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta observed a peaceful protest rally in Kharkiv where no attempts were made to storm the regional government building: “Most of the participants were students,” she said, “just half a thousand very young and unprepared kids who did not prepare for an assault at all”. Yet afterwards she saw on TV that an opposition politician was telling a Kyiv rally that “at this very moment protestors are blocking regional state administrations” in Kharkiv – and that the mayor of Kharkiv, from Yanukovych’s party, was threatening protesters that they shouldn’t involve themselves in a “war,” as they would be assured to lose it.

Violence and loathing on the streets

No doubt, the threat of violence and intimidation will have kept many away. Police used tear gas and smoke grenades, and “young men armed with baseball bats” attacked anti-government protesters in Kharkiv. In Zaporizhia, men “with white ribbons on their shoulders were walking around the city and beating people”, a local journalist reported. The BBC linked to videos showing vigilante titushki, armed with seemingly identical batons, gathering inside a Dnipropetrovsk government building and then rushing out to viciously beat up demonstrators. The local Governor later called these men “representatives of the region’s public organisations”, calling “everything … perfectly legal.”

Vice versa, eighteen policemen were injured in Dnipropetrovsk alone, according to regional authorities. A blogger in Donetsk described “hired thugs” being transported in on buses to stage mock street riots and “imitate assaults at official buildings,” presumably “to frighten people here and … mobilize their voters,” but it’s not as if actual attacks on administrative buildings by anti-Yanukovych protesters have been lacking in graphical violence of their own, as this disturbing footage from a Central-Ukrainian city illustrated.

Anti-government protesters in Kharkiv and Dnipropetrovsk talked to France24 about their motivations on January 27th. “[I]n Kharkiv we’ve been having protests every day since November 22,” said Natalka Zubar – but it’s tough going. “Here in eastern Ukraine, [..] Russian TV is even more popular than Ukrainian TV, and every day its anchors talk about LGBT people controlling all of Europe, spreading sodomy, things like this. They claim all protesters are hooligans. But I think that more and more people have stopped listening.”

Protesters from Donetsk at Euromaidan in Kyiv (Photo by spoilt.exile, creative commons)

Protests in Dnipropetrovsk started two months ago, added Pavlo Khazan, and “there had been no major incidents [..] until Sunday”. That day, however, “some protesters decided that we should go to the regional administration building. [..] When we arrived, we were shocked to see that, behind a line of police officers guarding the building stood hooligans armed with sticks and baseball bats. The police let them attack us, and then dispersed the crowd [..] and began making arrests.”

The slideshare touting the protests’ strength makes mention of football fans several times. There’s a long history of politics and football mixing, and Ukraine offers a new episode. Local fans of Metalist Kharkiv and Dnipro Dnipropetrovsk protected demonstrators from attacks by aggressive pro-government groups, AFP reported on the 31st, along with even fans of Shakhtar Donetsk, in Yanukovych’s own hometown. “We came to support our people in fighting for their rights,” explained some of a group of about 60 Shakhtar fans in central Donetsk.

Already back in mid-January, professor Alexander J. Motyl wrote a piece extolling the bravery of anti-government protesters in Donetsk: “at first, it was only a small group of about 20 to 30 demonstrators who repeatedly assembled at the Shevchenko monument [..]. Then, a few weeks ago, several hundred brave protesters [..] carried pro-democracy, pro-Europe, and anti-Yanukovych banners in a march through downtown”. Motyl argued that even these small numbers had the local establishment spooked, and compared the demonstrations with Martin Luther King’s civil rights marches through Alabama: “For 500 marchers to assemble in Donetsk is the equivalent of 50,000 in Lviv or 500,000 in Kyiv.”

Is it? In symbolic terms, maybe. But not necessarily in terms of measuring the balance of public opinion across the regions.

Fathoming public opinion

The Ukrainian Center for Social and Marketing Research SOCIS last week released the results of a poll it conducted between 17 and 26 January. They don’t include any regional breakdown, but the overall results are instructive. The opposition is definitely on an upswing: Klitschko ‘s UDAR, the pro-Tymoshenko Fatherland party, Solidarity, and the far-right Freedom party are pooling some 58-60% of the vote among them in both parliamentary and presidential match-ups. That’s about 10% more than these parties received in the 2012 parliamentary elections. (The parties now rallying in the streets already actually received a narrow majority of the vote back then, but lost out big in seats because of their divisions.)

Support for Yanukovych’s Party of the Regions, however, has barely lessened. The party would get 29% of the vote in parliamentary elections, and he himself is polling at 29-30% in presidential match-ups. In 2012, the Party of the Regions received almost exactly the same share of the vote: 30%. Instead, it’s the Communist Party which lost some of its vote, polling at 8% when it received 13% in 2012, and the largest shifts are actually taking place within the opposition camp, with Fatherland (down to 20%) and Freedom (down to 7%) losing out to UDAR (up to 24%) and Solidarity (9%). In addition, some 30% of the full, initial sample answered that they wouldn’t know who to vote for.

Yanukovych’s party won the 2012 elections by racking up 65% of the vote in the Donetsk region, over 50% of the vote in Lugansk and the Crimea, and some 40% of the vote in the regions of Kharkiv, Zaporizhia, Odessa and Mykolaiv. And the Communists hauled in 18-25% of the vote in those same regions. If the Party of the Regions remains at strength and the Communists hold on to at least half of their vote, as this new poll suggests, then a majority of those who have an opinion in these regions are likely still in their camp. In the Dnipropetrovsk region, the Party of the Regions and the Communist Party pooled 55% of the vote in 2012 while Fatherland, UDAR and Freedom added up to 38%, so if shifts are taking place roughly proportionally around the country, that region too would at best be evenly divided now.

In the same poll, respondents were given a straight choice between entry into the EU and entry into a Customs Union with Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan. A plurality of 43% chose for the EU, but 32% preferred the Customs Union (with the rest offering no answer), and that latter number will be proportionally higher in the East and South. These numbers suggest that little has actually changed. In openDemocracy, Valery Kalnysh recapped polling data from late December, when the Euromaidan protests were already ongoing but hadn’t yet escalated, and they showed that 50% of Ukrainians then supported Euromaidan while 42% did not, and that opponents were far in the majority in the East, by 65% to 30%. Tellingly, that poll had also shown support for not just the opposition leaders, but also Yanukovych going up since October, from 19% to 29% – suggesting that far from Yanukovych’s south-eastern base suffering erosion, the increasing polarization of the country was shoring it up. A whole series of polls by different pollsters between May and November 2013 had showed a similar balance of opinion, with support for EU access consistently at 41-47% and, with the one exception of a November poll, support for the Customs Union at 31-40%.

Rallying the counterforces: local authorities and the “titushki”

A view of Donetsk (Photo by Vladimir Yaitskiy, creative commons)

In some regions, the mere prospect of increasing protest did seem to change some of the political dynamics. In Odessa, the Kyiv Post reported, the local administration and opposition struck a truce of sorts, a “non-aggression, mutual supportiveness deal”. But elsewhere in the South and East, any challenge to the grip of Yanukovych loyalists seems to have been beaten back. On February 1, the Kyiv Post reported that local authorities in Dnipropetrovsk had detained two opposition party members for allegedly “plotting a terrorist attack at a national energy system facility”. In the Crimea, the regional parliament banned the Freedom party, though it was forced to reverse its decision on February 7. As January ended, one reporter found no more protests in Donetsk, just a middle-aged local scoffing: “Euromaidan? To hell with that!”. Organizers of a protest picket had cancelled it out of fear of further violence. Two local activists of the nationalist Freedom party had left Donetsk on the 27th, explaining that “we feared that emergency rule would be imposed so that nobody can leave the region”.

The regional deputy head of UDAR said that party activists throughout Donbass have been receiving threatening text messages on their mobile phones, and dismissed local pro-Yanukovych protesters as titushki, “hired thugs” and “former inmates”. An in-depth portrait of the “titushki” phenomenon for Foreign Policy describes these roaming groups of violent youths as an actually well-organized, 20,000-strong national force, complete with internal hierarchies, materially supported by riot police, and motivated by daily government pay-offs, Soviet and military-inspired loyalties to the state, ties to powerful organized crime groups with a vested interest in corrupt ruling politicians, and plain old criminal tempers.

Anton Davydchenko, the leader of a group called National Unity in Odessa which claims to have rallied over 1,000 volunteers, all ready to take up arms against anti-government protesters if necessary, would presumably recognize some of these descriptions and take issue with others. “We will never give them our cheek to be slapped. If they come to us with weapons, we will meet them with weapons,” he told RFE/RL. Like local authorities in Donetsk and Lugansk did with similar groups (described as including “Cossacks and Afghanistan war veterans”), local authorities are supporting the group.

Night over Kharkiv (Photo by Aleksandr Osipov, creative commons)

In Kharkiv, a conference of provincial Party of the Regions officials called for establishing a new organization called the “Ukrainian Front” – after the Soviet Army campaign that drove Nazi Germany out of Ukraine in WWII – at the suggestion of an Afghanistan veterans group. “‘The Front will purge and cleanse the Ukrainian land from anyone who has come here as an occupier,” orated the governor of Kharkiv: its participants “will follow their fathers’ and grandfathers’ example in freeing our lands, like in the 1940s”. (If that sounds alarming, it doesn’t help that many protesters in Kyiv have actually embraced the imagery of Stepan Bandera, who declared an independent Ukrainian State during WWII, and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), which committed war crimes and at times collaborated with Nazi Germany during its battle for independence.) Kharkiv’s eccentric mayor, Hennady Kernes, riffed on the same theme when approving of the local pro-Yankovych martial arts club Oplot, which has been accused of ties with the kidnapping and torture of Auto-Maidan leader Dmytro Bulatov: “I know these sportsmen,” he has said: “they are against allowing ‘Banderovtsy’ to come to Kharkiv and I support this”.

Map of the situation in Ukraine, 4 February 2014, Sergii Gorbachov

All in all, the authorities in the South and East seem to have succeeded in beating back any challenge which local protesters posed to their position in late January. The last time Sergii Gorbachov posted an updated map was on February 4, and all the South and East had reverted back to Yanukovych-blue, with added icons indicating the appearance of pro-Yanukovych demonstrators, Party of Regions brigades and violent “titushki” as well as local protesters.

Change: up to moguls or mobs?

In the end, if the protest movement is to crack the South and East in a meaningful way, it may not be up to the protesters themselves. It will have to be up to elements in the political class itself — “and no one within that class is more powerful than Ukraine’s oligarchs, the billionaire business tycoons who together own a vastly disproportionate share of the country’s wealth,” as Sergii Leshchenko wrote in Foreign Policy. They won’t be motivated by political idealism, but by self-interest, needing the doors to the EU to stay open, stability to return to the country, and themselves not to be targeted by financial and visa sanctions to protect their wealth. Leshchenko recounts how a second oligarch, Viktor Pinchuk, switched to supporting the opposition in December – and he’s from Dnipropetrovsk.

The others, however, are still hedging their bets, at best – and it would have to be someone like Rinat Akhmetov, Ukraine’s richest man and still powerful in his native Donetsk, to really overturn the dynamics. Lesser moguls will not do, as two of the richest businessmen in Dnipropetrovsk found out after January 25. That day, Hennadiy Korban and Borys Filatov decided to air live broadcasts of the antigovernment protests in Kyiv on a large outdoor screen at a shopping mall they owned, and hoist the flags of the EU and Ukraine at their local properties. Hours later, the New York Times recounted, the electricity was suddenly cut to all their three shopping malls. Four days later, a local judge ordered “that Mr. Korban be detained and interrogated as a witness in connection with a previously dormant investigation of a 2012 murder”. Then, state security officers raided the premises of the businessmen’s accountant for “bombs or other evidence of terrorism”. The two men have now relocated to Israel.

Enduring divisions

With the iron grip of local authorities from Yanukovych’s camp in the South and East seemingly barely letting up, for now, and indications that a majority of the population there is still on the opposite side from Euromaidan’s activists (who themselves are hardly unified), the question arises how much future there is for a unitary state so bitterly divided. The dividing lines today are, after all, not very different from the borders of previous eras – could they become real borders of one kind of another again? The Ukrainian Communist Party has floated a trial balloon: Ukraine as federal state. Dividing Ukraine up into seven large states, each with its own parliament, would pull the country back from the brink of civil war and prevent the country from falling apart, the communists argue. But the opposition, not altogether without reason, is likely to see this as a mere Russian strategy to break up the state and seize the South and East.

Despite the initial enthusiasm about unprecedented demonstrations in the East illustrated by the Monkey Cage blog post, it seems in fact unlikely that “Russophones and Ukrainophones, the East and West of the country, [..] ethnic Russians and Ukrainians” will really unite against the political forces represented by Yanukovych any time soon. On February 4, a week after the small protests in the South and East crested, an AP report concluded that “two months into Ukraine’s anti-government protests, the two sides are only moving further apart. [The protesters] appear unable to significantly broaden their movement into parts of the country where the opposition is weak, as some of the protesters use nationalist rhetoric that alienates even liberal eastern Ukrainians.” As David Stern wrote in The Atlantic, even if Yanukovych does steps down, peacefully, and the opposition assumes power, “it too would not resolve Ukraine’s crisis. Political divisions, both within the country and the protest camp itself, will remain, and possibly become more pronounced” over time.

![Egypt: "regime vs MB" score by governorate Egypt: "regime vs MB" score by governorate [Map]](http://observationalism.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/egypt_regime_vs_MB_score-300x300.png)

![Egypt: "Engagement score" Egypt: "Engagement score" [Map]](http://observationalism.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/egypt_engagement_score-300x300.png)