It’s a great relief for any democrat that Marine Le Pen’s Front National (FN) failed to win any region, after having led in six after the first round, and after Le Pen herself had prognosticated that the FN could win “four or five regions”. That would have been disastrous, not just in terms of policy but as signal of a new stage of far-right penetration, at a time when the politics of xenophobia is on the rise across Europe.

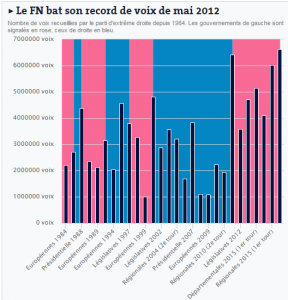

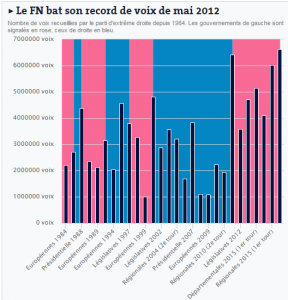

The Front National received a record number of votes in the second round of the regional elections

But the party still booked an all-time record result in this weekend’s second round, in terms of raw votes (see chart to the right, from here). 6.8 million votes went to the National Front’s candidates. That’s not just over 800,000 more than in the first round, but also more than voted for Marine Le Pen in the first round of the 2012 presidential elections. Which is all the more striking considering that there were 36.6 million votes in total in those, and just 26.5 million now. In the PACA region (Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur), for example, Marion Maréchal Le Pen led the FN list and received a whopping 45% more votes in this second round than Marine Le Pen had gotten in her presidential bid.

So Le Pen is still very well-placed to improve significantly on her 2012 result, when she received 17.9% of the vote in the first round, in the next presidential elections. A new opinion poll illustrates this. If Sarkozy runs for the right, Le Pen would get 27% in the first round, with Sarkozy and incumbent President Hollande both getting 21%, centrist candidate Bayrou 12% and leftist candidate Mélenchon 10%. If, instead, the more moderate Alain Juppé runs for the right (in which case Bayrou would drop out), he would get 29% of the first round vote, Le Pen 27%, and Hollande 22%.

In practical terms, the FN tripled its number of councilors. (See the charts in the right column here for the share of councilors it won in each region.) Due to France’s electoral system, the FN has always had trouble building a good bench of local and regional politicians, and this will help it expand that bench significantly.

Libération, meanwhile, highlighted the ground the FN has won in terms of the political discourse. It pointed to the mainstream right’s winning candidate in the Rhône-Alpes-Auvergne region, Laurent Wauquiez, as example; he recently published a piece which proclaimed “Immigration, Hollande, Brussels: ça suffit” (“that’s enough”). Marion Maréchal Le Pen had already announced before the first round: “we have won the battle of ideas, not that of the parties”.

In her concession speech, Marine Le Pen gave a taste of what her presidential campaign will sound like. She argued that the withdrawal of the Socialist Party candidates in two crucial regions proved that the left-wing and right-wing parties are all the same, and triumphantly announced that there is now a new new kind of “bipartisme” – not between left and right, but between “patriots” and “mondialistes”.

Along similar lines, Marion Maréchal Le Pen denounced “the cynical profiteers” of the traditional parties, against which the Front National likes to contrast itself so much as clean alternative and authentic voice of the people. “Our love of France has never been as exalted,” she told her supporters. The Front National mayor of Hénin-Beaumont, Steeve Briois, instead engaged in some projection, accusing “the republican front” of having “played on people’s fears and pursued a campaign of hate”.

Why the Front National failed to win any regions in the second round

Front National victories were prevented by a combination of three issues. One was that turnout increased significantly compared with the first round. As a result, the FN may have gained an additional 800,000 votes, but the other parties added a much higher number of 2,7 million voters to their tallies. It proved that there is still, for now, a “republican” majority for whom the FN is beyond the pale. A recent poll showed that 60% of the French think that the FN is “a dangerous party for democracy” and only 31% believes the FN is “capable of governing the country”.

The second reason the FN candidates fell short, surprisingly clearly in the case of Marine Le Pen herself in the Nord-Pas de Calais-Picardie (NPDCP) region, was that the Socialist Party withdrew its candidates in crucial regions. In the NPDCP and PACA regions, Marine and Marion Maréchal Le Pen had received over 40% of the vote in the first round, with the candidates for the traditional right-wing lists behind by over 14 points and the left’s candidates in third place. In both regions the left’s candidates retreated in order to block the Le Pens. In the northeastern region Alsace-Champagne-Ardenne-Lorraine, the Socialist Party withdrew its support from the Socialist candidate there who insisted on proceeding to the second round against its advice.

In Nord-Pas de Calais-Picardie, Socialist activists went as far as leafleting for the right-wing candidate to help stop Le Pen. While the Socialist withdrawals lead to “an explosion of blank votes” in those two regions, as some left-wingers went to the polls but refused to vote for either candidate, the mobilization of a “republican front” was nevertheless impressive. In the left-wing first ‘arrondissement’ of Marseille, for example, the left’s withdrawal and support boosted the traditional right-wing candidate’s results from 17,7% in the first round to 80,1% in the second round.

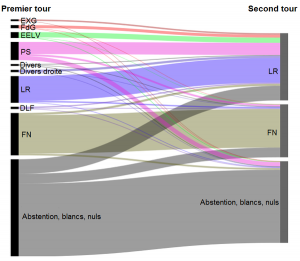

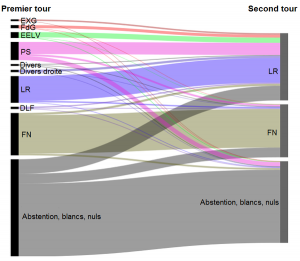

France regional elections: vote transfers between the first and second round in the two regions where the socialist candidate withdrew

The chart to the right, showing the pooled voter flows in the PACA and NPDCP regions, shows it nicely as well. The increase in turnout in the second round benefited both the traditional right and the far right, but the former more so than the latter. Most importantly, however, it looks like almost a third of the vote for the victorious traditional right’s candidates came from left-wing voters. The picture was much more straightforward in the other regions, which had three-way run-offs with left-wing, right-wing and far-right candidates, though again it’s noteworthy how the increased turnout benefited the former two much more than the FN.

The Socialists paid a heavy price for this exercise in civic spirit though. Nord-Pas de Calais had been one of the left’s traditional strongholds; the Socialists came first in every regional election there since the region was created in the mid-1980s. Now, the Socialist Party will not have any representatives in the regional assembly, nor in PACA.

Third, the FN leads in the first round were partly deceptive because of the role smaller parties played. The Socialist Party may have received just 23% of the vote in the first round, but various green and leftist candidates received an additional 13%, and those formed a natural reserve of additional second-round votes for Socialists who made the run-off. The traditional right could at least to some extent fall back on voters from the Gaullist, Eurosceptic “Arise France!”. But there are no smaller far-right parties of note which the FN can draw on in run-offs.

For example, the Socialist Party candidate in Bourgogne-Franche-Comté placed third in the first round, with 23% of the vote against 24% for the traditional right’s candidate and 31% for the FN candidate. But in that same first round, 12% voted for other left-wing candidates, who collectively put the left at 35%; and 8.5% of them voted for Arise France! and the center-right MoDem, which would put the traditional right at a total of 32.5%. There were no minor party candidates which provided a pool the FN candidate could draw from. From this perspective, the second round result was no surprise at all, since it almost exactly reflected the proportions of each “camp” (as wide-ranging and eclectic as those are) in the first round: 35% for the left’s candidate, 33% for the traditional right, and 32% for the FN.

The results and challenges for the left and (traditional) right

The end result, in which the left won five regions against seven regions for the right, was a better than expected result for the left. “At the beginning of the campaign,” the conservative Figaro wrote, the socialists “had hoped to hold three regions at most”. But Le Monde published a chart which emphasizes an important distinction: the regions the right won have twice as many inhabitants as the ones the left won. This is in no small measure due to the right winning “Île-de-France” (Greater Paris), which Libération called the country’s “mammoth region of 12 million inhabitants”. The loss of Île-de-France smarts all the more because the left had held it for the past sixteen years.

By ways of symbolic comfort, @Taniel pointed out, the Front National was very weak in the two Paris arrondissements where last month’s terrorist attacks occurred, getting just 5% of the vote there while the left romped home.

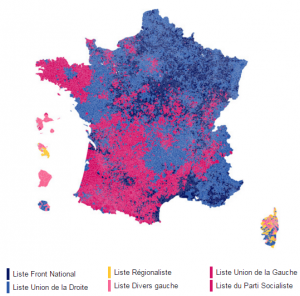

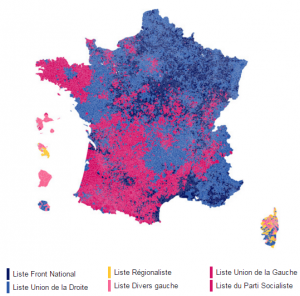

Regional elections in France: results of the run-off, by commune. Source: Le Monde.

The less-disastrous-than-expected result is still likely to reignite a long-standing fight within the Socialist Party. What should the strategy be, ahead of the next presidential elections? As Le Figaro wrote: “In a landscape where three political parties compete in the first round, with an advantage for the Front National, the crucial objective is to make it into the second round. But how? By achieving, foremost, unity on the left, or by trying to quickly search for voters in the centre? It’s this question the socialists will now struggle to answer, knowing that it divides them deeply.”

Sarkozy’s supporters on the right and center-right face similar, perhaps even more combustive internal arguments, however. Nathalie Kosciusko-Morizet, the vice-president of Sarkozy’s party who had already earlier openly dissented from his line, pointedly remarked last night that if the left had applied the same “neither-nor” line which Sarkozy imposed on the right, obliging its candidates to refrain from any kind of alliance with the left against the FN, the right “would have lost”. The right’s candidates in the PACA and NPDCP regions seemed well aware of this, making sure to thank the left’s voters. But Sarkozy’s line has strong allies too, like the above-mentioned Laurent Wauquiez. [Edit: One day after I wrote this post, Sarkozy had Kosciusko-Morizet fired and replaced by noone else but Wauquiez.]

What will complicate this fight is that there will likely be an additional argument over when the right’s presidential primaries should be held. If the right’s contenders, like Sarkozy and Juppé, are waging a bitter fight until shortly before the presidential elections themselves, this could harm them and create opportunities for a Left vs FN run-off. But aspiring contenders who are currently further back in the primary polls, like former PM François Fillon, want the extra time, Le Figaro explained. To add to the complications, Sarkozy seems like the front-runner, but the polls show Juppé doing much better in a run-off against Le Pen.

Education, income and partisan preference, France & Netherlands edition

A French polling outfit called OpinionWay did a survey for Le Point about who voted what in the second round of the regional elections, and the breakdowns by education and income are stark. They also happen to echo findings by Maurice de Hond’s polling outfit this weekend in the Netherlands.

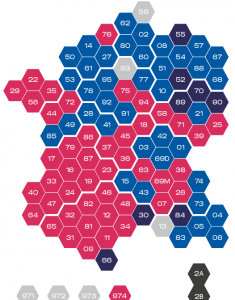

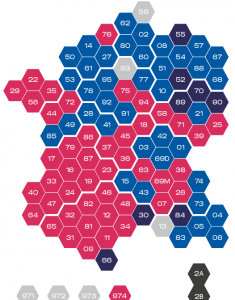

Another way of visualizing the run-off map: leading party/candidate by “département”. Source: Liberation

Breaking down results by three educational levels, OpinionWay found that a whopping 44% of lower-education voters voted for the Front National, while just 16% of higher-education voters did. Both the left and the traditional right did better among higher-education voters, and both — perhaps surprisingly — by roughly the same margins.

Among professional categories, workers (“ouvriers”) went for the Front National by a stunning 54% to 26% for the traditional right and just 20% (!) for the left. The unemployed, however, spread their votes evenly among the three camps. But another set of data from the survey shows that turnout among them was a bitterly low 36%.

The Front National also easily led among those with the lowest incomes (less than 1,000 euro/month), attracting 43% of them to 34% for the traditional right and just 23% for the left. The left came closest to leading among the upper middle income category of 2,000-3,500 Eu/m, getting 34% of their votes to 38% for the traditional right and 28% for the FN. The traditional right did best among the uppermost income category, getting 47% of its vote.

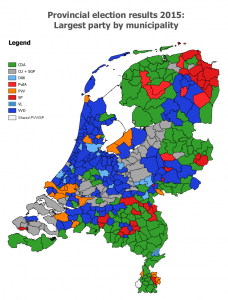

The Dutch poll had shown the far right with similar, dominant leads among lower-education voters. According to de Hond (also using three education-level categories), Geert Wilders and his Freedom Party are getting 37% of the lower-education vote, and just 14% of the higher-education vote. Almost half (46%) of lower-education voters would consider voting for the Freedom Party, vs just 20% of higher-education voters. The only other party whose support is slanted towards the lower-educated is on the opposite end of the political spectrum: the Socialist Party gets 13% of the lower-education and 7% of the higher-education vote. (“Would consider” voting for the Socialists: 28% vs 17%.)

Conversely, the liberal and conservative center-right parties (VVD, CDA and D66) are pooling a strong 48% of the vote among higher-education voters, but just 22% of the lower-education vote. It’s a serious cleavage, which has shown up in surveys in the Netherlands for years now, and seems much more pronounced than class-based cleavages in earlier decades. It’s a serious cleavage, which has shown up for years now, but seems so much more pronounced than class-based cleavages in earlier decades.

It’s also an arguably much more damaging cleavage. In the post-WW2 era, the Dutch working class disproportionally voted for the Labour Party (though the christian parties also always received a substantive chunk of the working class vote), and the Labour Party regularly got to govern, ensuring that working class interests would at least sometimes be met. As a result, working-class voters had some reason to retain an extent of confidence in the political system. However, neither the Freedom Party nor the Socialists in the Netherlands, nor the Front National in France, are likely to gain entry to government (and in the case of the far right parties wouldn’t do much constructive on behalf of working class voters even if they did). Meanwhile, the Dutch parties that are most amenable to coalition governments, like the VVD, CDA and D66 as well as the Labour Party, have less reason than ever to prioritize working class interests, since that’s not where their electorate lies (anymore). The political cleavage therefore threatens to lock working class voters in an anti-systemic camp, as that’s where the only parties are which appeal to their interests and sentiments, but those parties won’t be able to represent their interests in governmental policy and the other ones will have less reason to do so; all of which in turn will only erode any confidence working class voters have left in the system. It could be a real vicious cycle.

As you’ll have guessed, that was the Minnesota race between Al Franken and Norm Coleman. The two men raised $20.5 million and $18.0 million, respectively. That translates to $488 thousand and $430 thousand for each percentage point of the vote they ended up winning – which ranks Al and Norm as #1 and 2 when it comes to raising the most money per percentage point won.

As you’ll have guessed, that was the Minnesota race between Al Franken and Norm Coleman. The two men raised $20.5 million and $18.0 million, respectively. That translates to $488 thousand and $430 thousand for each percentage point of the vote they ended up winning – which ranks Al and Norm as #1 and 2 when it comes to raising the most money per percentage point won. Your vote was worth most up in Alaska. Mark Begich raised a total of $4.4 million – which translates to a royal $29 for every single vote he received. His opponent, Ted “bring home the pork” Stevens, was right up there too and raised a stunning $26 per vote – in vain.

Your vote was worth most up in Alaska. Mark Begich raised a total of $4.4 million – which translates to a royal $29 for every single vote he received. His opponent, Ted “bring home the pork” Stevens, was right up there too and raised a stunning $26 per vote – in vain.