Last weekend the citizens of Dresden went to the polls for the first round of elections for Oberbürgermeister, an office which Wikipedia translates as Supreme Burgomaster. That sounds funny. Let’s just say mayor.

The incumbent Helma Orosz, from Angela Merkel’s Christian-Democratic Union (CDU), had resigned in February – she suffers from breast cancer. The liberal FDP’s Dirk Hilbert took over her tasks for the few months since, and he ran in these elections as an independent candidate. His main opponent was (and remains) Eva-Maria Stange, a politician from the social-democratic SPD who is running as independent with the support of the SPD, Left Party and Greens. Hilbert’s bid was complicated by the CDU running its own candidate, and there were also two candidates from the populist (far) right. In comparison, Stange had little competition on the left – nobody but Lars Stosch, alias Lara Liqueur, from the satirical party The PARTY, who promised free beer and equal representation for lazy people.

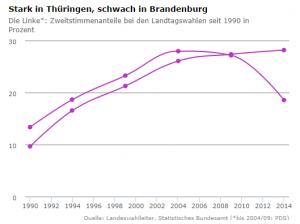

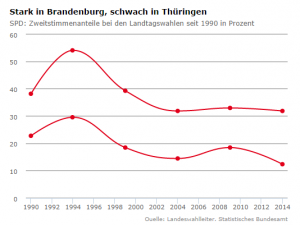

Although Merkel’s CDU dominates the national party landscape, getting 41.5% of the vote in the 2013 parliamentary elections against the SPD’s 25.7%, Dresden was actually the last German city with over 400,000 inhabitants to still have a CDU mayor. But as capital city of the eastern state of Saxony it was a good place for it, since Saxony is a bit of a Christian-Democratic bulwark. The CDU actually used to get absolute majorities in state elections in the 1990s, and in last year’s state elections got 39% to the Left Party’s 19%.

Dresden itself has in the past been more politically balanced. In the municipal elections of 2014, the Left Party, Greens, SPD and Pirates pooled 52.7% of the vote (and yes, that was their ranking order), while the CDU and FDP pooled just 32.6% and the populist and far right (AfD and NPD) got almost 10%. But in the previous elections, in 2009, the left-of-center parties got just 44%, the CDU, FDP and DSU also pooled 44%, and the extreme right got 4%. Moreover, in the last mayoral elections – which took place all the way back in 2008 (seven-year terms!) – Helma Orosz almost got the 50% of the vote required to be elected in the first round, and eventually defeated the Left Party’s candidate by a massive 64% to 31% margin in the second round.

Orosz remained a popular mayor, but there was confusion on the right after she resigned. Her own party nominated Saxony’s Interior Minister Markus Ulbig, but he proved to be a weak candidate. Dresden was at the center of the mass rallies by the anti-Islam movement Pegida (as illogical as that might seem, considering that the city has very few muslim residents and just one mosque, and 80% of the population is secular), and Ulbig’s vacillating response managed to piss off both Pegida supporters and their left-wing opponents.

Instead, Hilbert became the center-right’s de facto main candidate. But on the far right, Pegida had its own candidate, the independent Tatjana Festerling, who likes to tell her supporters that the “professional politicians”, and especially those of the left, are just “alcoholics, communists and childfuckers,” and that a “flood” of asylum-seekers will increase crime. Festerling is too radical even for the upstart populist right-wing Alliance for Germany party (AfD), which sent its own candidate into the contest: Stefan Vogel.

The polls had foreseen a first round advantage for Stange, with Hilbert right behind and Ulbig merely in third place. That all turned out to be true, and with just 15% of the vote the CDU candidate was even further behind Stange (36%) and Hilbert (32%) than the polls has suggested. This means that, however the second round ends, the CDU will no longer have a mayor in any of Germany’s largest cities.

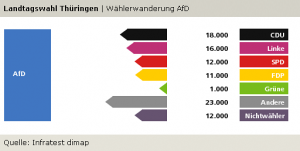

What the polls got all wrong was the far right’s appeal. Festerling did not merely get 1-3% of the vote, as they had indicated. She got 9.6%. And Vogel got another 4.8%.

Festerling did especially well in the city’s communist-era high-rise suburbs, like Gorbitz, which were partly torn down when they emptied out in the 1990s (Gorbitz itself used to have a population of well over 35,000; now it’s 21,000, though trending up again). Those neighbourhoods generally are a source of strength for the Left Party as well, but in this election the left/right divide mostly ran parallel to the divide between inner Dresden and the suburbs.

Saxony is an odd case in the sense that second round elections are not run-offs. They’re more of a re-run. Nobody gets eliminated after the first run; in principle, all the candidates are allowed to run again. (Baden-Wurtemberg has an even stranger system; there, even new candidates can still enter the race.) In practice though, it doesn’t work like that. Ulbig announced immediately after the first round that he would not stand in the second round and wanted to talk with Hilbert about an agreement. Perhaps more surprisingly, Festerling later withdrew as well and went further, quite stridently appealing to her supporters to vote for Hilbert. The state AfD joined in as well: the party’s primary aim should now be “to prevent a victory for the leftredgreen candidate and former SED member Stange”.

All of this suggests that Hilbert, rather than Stange, has the advantage going into the second round, which will take place on July 5. After all, when you add up the results for all the right-of-center parties, that’s 61.5% of the first round vote. No wonder that Stange has promised to “mobilize non-voters”. And that’s easier said than done too; in fact, the turnout in the first round was already unusually high, at 51% compared to the previous mayoral election’s 42%. Presumably that was thanks in large part to Festerling success in mobilizing protest voters who would normally not bother to show.

Yet things might not be quite as straightforward, as at least one local political scientist argues. Most of Festerling’s voters will probably stay home, he says. There’s certainly no organic link between Hilbert and Festerling’s voters: he did badly or very badly in many of the neighbourhoods she did best in. The supporters attending the rally where she made her endorsement certainly didn’t seem happy about it.

Moreover, Hilbert has so far done his best in his campaign to present himself as a moderate, almost neutral candidate who stands above party politics, and distances himself from both left and right. But now Ulbig and the CDU, and Festerling in her own way, are pushing him to wage more of a “Lagerwahlkampf” – an election campaign between two camps, left and right. How else is he going to rally their voters in a low-turnout election? But he doesn’t seem eager. He’s rejected the concept of a “Lagerwahlkampf” outright; refused to meet with Festerling, even as he also refused to repudiate her support; and surprised the CDU by ruling out a written pre-election agreement with any party.

Is he being smart, or shooting himself in the foot? Maybe Stange still stands a good chance after all.