Update: see also this post about the provincial elections of 2015 in the Netherlands – it has better maps and dives into some electoral history as well.

It’s not easy for local elections in a country the size of The Netherlands to make the international news. But if there’s anyone who can make it happen, it’s the peroxide-blonde leader of the Dutch far right Freedom Party, Geert Wilders. And that’s what he did, on March 19, when the municipal election results were being tallied.

Orating to a Freedom Party rally in The Hague, Wilders asked his supporters to give “a clear answer” to three questions that he was going to ask them; three questions that “defined our party”. “Do you want more or less European Union?”, he started off. Less, less, his supporters chanted enthusiastically. Second question: “Do you want more or less Labour Party?” Again, the crowd clapped and chanted: “less, less!”. So Wilders moved on to the third question. “I’m really not allowed to say this,” he started, but “freedom of expression is a great value … so I ask you, do you want more or fewer Moroccans, in this city and in the Netherlands?” The crowd, elated, chanted back: “Fewer, fewer, fewer!”, and with a sly little smile Wilders remarked, “then we’ll go and arrange that”.

Which got the Dutch election night headline space from the BBC to The Guardian, from the Times of Israel to Al-Jazeera, and from Fox News to the Huffington Post.

All of which was pretty unfair, considering that Wilders’ Freedom Party (or the PVV, as the Dutch call it) had been something of a non-entity in the whole local elections campaign. The party had refrained from taking part in the elections altogether in all but two municipalities: The Hague, the seat of the Dutch government, and Almere, a large town in Amsterdam’s commuter belt. Moreover, as was mentioned in almost none of these stories, it actually lost votes in both cities.

The backlash: Wilders had mostly eschewed municipal politics to avoid disorder, but that’s what he got

So why was the PVV not taking part in more municipalities? Wilders isn’t too keen on building a nation-wide party organization with a variety of local branches; the party doesn’t even have a membership structure. It remains the personal vehicle for Wilders and his art of provocation, and he likes it that way: no internal party democracy, no bothersome national conferences, and as few potentially wayward local sections as possible. That’s presumably the lesson he learned from the List Pim Fortuyn (LPF) debacle. After Fortuyn’s assassination in 2002, the party that bore his name, which he’d only just, hastily established, became a carnival of dilettantism and embarrassment, filled with nuts and crooks, and marked by endless infighting between cliques and factions. Thanks to Wilders’ approach, the PVV has at least been quite stable, in comparison. Most PVV scandals now are of Wilders’ own, deliberate, making. I suppose that his reasoning, with these as well as the previous local elections, must have been that it was better to forego on translating the party’s excellent polling into lots of local councillors than to risk disorder and divisions.

That wasn’t going to stop him from hijacking the election night’s media coverage, though. The best of both worlds!

The backlash he must have eagerly anticipated might have been bigger than he’d expected, however – his later assertions that he was only talking about “criminal Moroccans” notwithstanding. Bigger than I would have expected, in any case, considering all Wilders had gotten away with in the past. Prime Minister Mark Rutte condemned the remarks, saying they had “left a bad taste” in his mouth. Thousands of people demonstratively reported Wilders’ remarks to the police for discrimination and incitement to hatred. The German press agency DPA compared Wilders’ rhetorics with those of Joseph Goebbels, and the news editors of the commercial broadcaster RTL published an open letter condemning the remarks. Ethnically Moroccan Dutch citizens started a Twitter campaign with the hashtag #bornhere, brandishing their passports.

Most surprisingly of all, some of his own party representatives started bolting. By March 24, two of his party’s remaining 13 MPs (a fourteenth MP had left earlier) had abandoned the party. So had its leader in the European Parliament, Laurence Stassen; and Stassen’s replacement announced he would not run again this year. Five of the party’s provincial deputies broke with the PVV, including two of its three deputies in Frisia. The party’s freshly elected nine councillors in Almere collapsed in a protracted 48-hour psychodrama, with eight of them releasing a statement criticizing Wilders’ remarks and initially expelling the ninth, Wilders-loyal councillor. Since then, more provincial deputies have left, and the party has now lost about one in six of them in total. It will survive though; after dipping from some 25-27 to 20-22 seats in the wake of that night’s events, the PVV is now riding high at 24-25 seats in the national polls again now (i.e. some 16%), compared to the 15 (or 10%) it has now.

The actual elections winners: the Democrats (D66) and the Socialists (SP)

All of this hullaballoo around Wilders was, needless to say, tremendously unfair to the political parties that actually contested the local elections on a meaningful scale. It was particularly unfair to the Democrats (D66), and to a lesser extent the Socialist Party (SP), who were the big winners.

To be sure, it was the local parties which actually made the most gains, upping their share of the vote by five percentage points to almost 30% (and a total of 2,819 local councilors), and in the process depressing the vote for almost all the national parties. And it’s worth observing that these local parties, once mostly the reserve of rural or small-town municipalities, have been making major inroads in cities as well: “Livable Rotterdam,” which first surged out of nowhere into first place when Pim Fortuyn was still its leader, returned into first place again this year, and local parties called Better for Dordrecht, Emmen Awake, Municipal Interests Deventer and Pro Hengelo topped the polls in other cities that rank among the 40 largest in the Netherlands.

D66's Alexander Pechtold's stemfie: Bit sad for the party's local no. 1 candidate to know his own party leader didn't vote for him, maybe?

But their successes, other than Livable Rotterdam’s (which is ideologically aligned with the Freedom Party), are fairly irrelevant to national politics, so it’s more interesting to look at how the national parties fared – and the Democrats did best of them all, gaining an additional 280 local councilors or so. With their new total of 824 council seats and 12% of the vote, they are now the third largest party in local politics. Most eye-catchingly, the Democrats became the largest party in Amsterdam, The Hague and Utrecht – i.e. in three of the country’s four largest cities. The victory in Amsterdam was fairly historic, too: it was the first time since the end of World War 2 that the Labour Party did not come out on top in the city. The Democrats also topped the polls in an array of medium-sized cities, especially university towns and towns in the west or center of the country: Tilburg, Groningen, Enschede, Apeldoorn, Haarlem, Amersfoort, Zaanstad, Arnhem, Zoetermeer, Leiden, Delft, Hilversum.

The Socialist Party (SP), meanwhile, almost doubled its number of councilors, from 249 to 440 (all of whom, it’s worth mentioning, transfer 75% – or in the four big cities, 50% – of their financial compensation to the party), and increased its vote share from 4.1% to 6.6%. The SP is traditionally strongest in the south-east of the country, where it long fostered local bulwarks such as Oss even back in the 1980s and early 1990s when it had no national representation at all. Since then, however, it has also started encroaching on traditional Labour areas, especially Labour’s heartland in the northeast. That development accelerated in these elections, with the SP actually taking over from Labour as largest party in the small-town northeastern muncipalities of Oldambt, Hoogezand-Sappemeer and Bellingwedde. In both the latter municipalities, the Labour Party had been the largest party since at least WW2 – in fact, up til 1990 Labour used to get over 50% of the vote in Bellingwedde.

The biggest prize the Socialists took, however, was the traditionally leftist university town of Nijmegen, where the Green Left had been the largest party previously. The Socialists also remained the largest party in the former mining city of Heerlen. Beyond those two, the only other town among the largest 40 municipalities where it topped the polls was Helmond, in the south-eastern countryside. Its best result (29.5%) was in Gennep, near to party leader Emile Roemer’s home town.

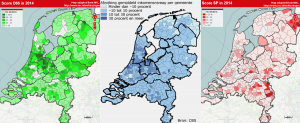

In general, the SP’s electoral map shows that it is building an electorate especially in the peripheries, expanding from its traditional base in the historically catholic part of the country. The party has a long tradition of local roots in eastern Brabant, in particular, where the SP was getting over 20% of the vote in Oss even when it was still a Maoist splinter with a national vote of just 0.3%. Its brand of local and neighbourhood activism apparently fit especially well with the clientalist tradition of local Catholic politicking, and maybe made it easier for voters to shake off the stern threats against voting for the “reds” by yesteryear’s priests which had traditionally kept the Labour Party, seen more like outsiders from the West, weak in the south. In fact, comparing the 2012 elections map for the SP with that of catholicism in the Netherlands suggests a definite correlation.

However, especially with its gains in the northeastern province of Groningen, the party seems to be more broadly developing an electorate in the small-town, often economically ailing, regions furthest away from the bustling cities in the West. The party suffered one awkward loss, however; in the small southern town of Dongen (pop. 25,000), where the party has been getting double-digit percentages since the mid-1980s, reaching a peak of 24% in 1994, and where it had received 19% of the vote last time round, it had to pass on taking part altogether this time. It simply could not find party stalwarts willing to take on the job of town councillor.

Pulling in opposite directions: the election winners and the role of class

There are, of course, several systemic problems when trying to extrapolate broader lessons about the state of national politics from local election results. As mentioned, local parties took a hefty, increased share of the vote, and no longer just in rural areas, and their success can not be trusted to harm all national parties in proportionally equal ways. The Freedom Party, one of the most important national parties, hardly took part (and its voters in particular seem to have added to the local party vote). Local policy issues and local politicians play a significant role in the election outcome, more so than in provincial elections – unusual election results will often be due to local controversies. Even local chapters of the national parties can be quite varied in orientation, as becomes clear from spending some time on the local vote-match sites that appeared during the campaign – one of which was used almost a million times. In Delft, for random example, the Labour Party turns out to be surprisingly right-wing, while in Heerlen the Green Left party appears to have a fairly neoliberal approach.

In addition, a relatively small number of municipalities did not take part in these elections, having already had interim elections during the last four years after, for example, a merger of municipalities. Most notably, Den Bosch, Leeuwarden, Alphen aan den Rijn, Alkmaar, Oss, Spijkenisse, De Friese Meren and Heerenveen had no elections. Turnout is lower than in national elections and seems to ever decrease – this year just 54% of the country’s eligible voters came to the ballot box, a record low – which benefits the parties with the most loyal and disciplined voters. And finally, while larger municipalities do also have larger councils, the increase is not scaled proportional to population size, and thus smaller municipalities have a disproportionate weight in the results when measured by total number of council seats won.

Not that this will stop commentators from observing national trends – not me either. Because despite all the above, those can still be easily discerned.

The gains being made by the Socialists and Democrats, not just in these local elections but in the national polls as well, for example, are of very different nature – but the one thing they have in common is that they both largely take away from the Labour Party’s support. The Socialist Party’s appeal, at least in the national polls, is in some ways similar to that of the far-right Freedom Party. Both parties do well among lower income classes and lower education groups. Both do weakly among higher income and education classes. The Freedom Party fares better than the Socialists among middle classes.

This largely class-based appeal of the new, populist parties has made the Labour Party, the country’s traditional working class party, exceptionally vulnerable. (The Socialist Party first entered parliament in 1994, and only reached a double-digit number of seats in 2006; the Freedom Party builds upon the electoral breakthrough of the List Pim Fortuyn in 2002). While those who stuck with the Labour Party through the rise of the far right in the last decade are unlikely to switch to the PVV after all now, the Socialist Party remains a popular alternative for those who feel alienated by the Labour Party’s liberal policies in government. The Volkskrant noted how the Labour leadership has basically chosen for a time-tested strategy: governing from the right and campaigning from the left. They even handed out half a million red roses. But it failed to convince anyone.

The working class seems to have been all but lost as safe haven to the Labour Party. When the social-democrats surged back into a solid second place in the 2012 elections thanks to a strong campaign and the personal appeal of its new leader, after having badly trailed the Socialists in the polls for months, it was thanks only in part to recapturing some of that old base. The party received 29% of the low-income vote and just 19% of the high-income vote; but in a sign that it was hardly a return to the old days, the party actually did better among mid-level and higher education voters (25-26%) than among low-education voters (23%).

Since then, things have gotten worse than ever for the Labour Party, and they have suffered as much among working class voters as among all voters. In a poll from last February, just 12% of low-income voters and 6% of low-education voters expressed a preference for the Labour Party. It’s the Freedom Party and the Socialists who now dominate among those groups. They pool 56% of the low-education electorate (33% for the PVV, 23% for the SP) and 47% of the low-income electorate (23% for the PVV and 24% for the SP). They dominate among lower-middle income voters too (26% for the PVV and 19% for the SP).

The Labour Party has seen bad times in the polls before, and sometimes – like in 2012 – recovered in time for the elections. But these numbers are setting new records. In the summer of 2012, when the Labour Party was languishing in fourth place in the polls, it could still muster 12% of the vote among lower-education voters; now it’s down to half of that, and the party’s actually surviving best (10%) among higher-education voters.

In recent months, political momentum has shifted from the enduring Freedom Party’s popularity (and to a lesser extent the SP’s) to a very different kind of party. D66’s political appeal is roughly the mirror opposite of those of the PVV and SP. And in the wake of its big wins in the local elections, the party has leapt into first place in the national polls.

While the PVV and SP feed on resentment of the government’s liberal austerity policies, the Democrats are edging the government parties on from the outside. D66 leader Pechtold went as far as calling his party “his Majesty’s most loyal opposition”; if it blames the VVD and Labour Party for anything, it’s for not going far enough with their economic reforms. While the PVV and SP steer a course of near-total opposition to everything the government does, D66 is eager to prove itself constructive and cooperative. A few months ago, when the government risked stumbling over its lack of a majority in the Senate in a crucial vote, it entered into a formal agreement with D66 and two small Christian parties, in which those opposition parties vowed to support the government in forthcoming parliamentary votes in exchange for some policy compromises, with the Democrats priding themselves in particular over additional investments in education.

While the PVV and SP appeal to lower-education and lower- and middle-income voters, D66 firmly targets higher-education voters. It is exceptionally popular among students, and the saying used to be that the Democrats were the party which people with a high education voted until they had enough money to switch to the VVD. But the Democrats are now also firmly making gains in the highest income brackets. The February poll had the party’s support among higher-education voters six times as high as among lower-education voters, but also almost three times as high among higher-income voters as among lower-income voters. This was confirmed in the local elections: the party’s second- and third-best results were in the university cities of Leiden and Utrecht, but its best result was in Haren, a leafy village outside Groningen, and the wealthiest municipality in the North’s four provinces.

Historic lows: the Labour Party’s losses

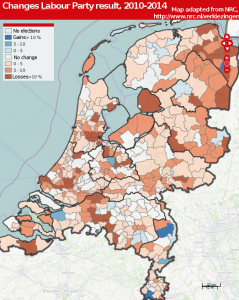

While the Democrats must have gained from the weakening VVD as well, their gains and those of the SP were most of all the Labour Party’s losses – and as mentioned already, these included some historic defeats. In total, the Labour Party (acronym: PvdA) lost over a third of its local council seats and its share of the vote dropped further from 16% to 10% – easily its worst result ever. And to think that just eight years ago, the party still received 23% in the local elections, beating out even the aggregated total for local parties!

In the city of Groningen, the Labour Party lost its top position for the first time in over sixty years. In Enschede, it was lopped off its top position for the first time since at least WW2. The same was true in Emmen. In Deventer, too, this was the first time since at least WW2 that the PvdA did not come out on top. Same in Gouda. It’s not all that many years ago that the Labour Party would get 40% of the votes in Amsterdam and 50% in Rotterdam; now it was down from 29% to 18% in Amsterdam and down from 29% to 16% in Rotterdam.

In the province of Groningen, where it traditionally does better than anywhere else, it suffered especially. The party now came out on top in just one municipality in the whole province, and six of the seven municipalities where the party lost most were in that province (just like four of the seven municipalities where the Socialists gained most were there). In Hoogezand-Sappemeer, it lost five of its eight seats. (Its worst result was elsewhere, though: in the southern municipality of Oosterhout, it lost four of its five councillors.)

The loss of votes has inevitably also led to a loss of city government positions – disproportionally so, it seems. It will no longer be part of some 50 of the 178 city governments it participated in before. In Utrecht the Labour Party will be absent from the city government for the first time in at least sixty years, as an unlikely combination of D66, Green Left, the VVD and the Socialists will try governing together instead. In Maastricht, where a party for the elderly became the largest party, Labour will not take part in the city government for the first time in almost seventy years. Labour and the Christian-Democrats had governed the city from 1946 to 2010, but now a diverse coalition of the local “Seniors Party,” D66, the Socialists, the Green Left and the VVD will take office.

As these examples show, there is a long tradition of broad coalitions in Dutch local government, uniting parties from left, right and center in pragmatic collaborations. Nevertheless a centrist party stands a better chance of local government posts than a party whose ideological leanings are all too explicit. Thus, no less than 9.5 of the some 17 million Dutch will live in municipalities where at least one of the aldermen is a Christian-Democrat. More than half of the Dutch will have at least one D66 alderman. But the Socialists will remain outside the local government even in half of the municipalities where it became the largest of nationally operating parties. Still, in addition to Utrecht and Maastricht, the southern cities of Eindhoven, Tilburg and Breda, as well as Arnhem and Nijmegen in the east – and Almere – will get SP aldermen (or -women). Negotiations in Amsterdam, meanwhile, are still completely stuck.

The Labour Party is in an impossible strategic situation: it suffers an exodus of voters to both D66 and the SP, but those voters, demographically, are each other’s opposites and are leaving the Labour Party for opposite reasons. The voters who have headed, and keep heading, to the SP feel that the Labour Party has lost its left-wing soul. They tend to be gloomy about the country’s economy as well as their own financial perspectives, look to the government to shore up the social protections of the welfare state, and be angry that the Labour Party is instead “selling out” to the VVD, to big business, to the EU. But the voters which are deserting the party for D66 are fairly optimistic about the economy and their own perspective, warmly favour EU integration, and might only be afraid of the country “missing the boat” by not demonstrating enough dynamism and adaptability. They are presumably attracted by the Democrats’ supremely vague, feel-good slogans, which read like haikus of vacuousness (“Different / Yes / D66”, “And now / forward / D66”, “D66 opens / Doors / Opportunities / Dreams”), which mask the party’s ongoing shift from its center-left, social-liberal roots to a more purely (neo)liberal profile. The net result is that any move the Labour Party might make to win back the voters on one side will likely just further increase its bleeding on the other side.

The VVD’s scattershot losses

The other government party, the right-wing liberal VVD, lost significantly too. It shed 334 of its 1,430 or so council seats, and fell from 16% to 12% of the overall vote. In the city of Groningen, it lost half of its six seats. In rural municipalities like Losser, Oost-Gelre and Maasdriel, it lost even more. But there seems less of a structural character to the party’s losses, and none of them amounted to firsts in post-war history.

Some of its worst losses were clearly tied to local shenanigans and rivalries. Most notably, veteran VVD politician Jos van Rey (a former MP and Senator who was last a city alderman in Roermond) had been expelled from the party after becoming the subject of a police investigation into corruption and vote-buying, but responded by founding his own “Liberal People’s Party Roermond,” taking most of the local VVD politicians with him. His new party promptly won 10 of the 31 council seats, while the VVD collapsed from 11 to 3. In Roosendaal, the VVD lost five of its nine seats but a rival, local Free Liberal Party gained five; in Heemskerk the party didn’t even contest the elections after intra-party turmoil culminated in death threats.

Less widely reported than the party’s troubles with Van Rey in Roermond, the VVD had problems in its very heartland too. Wassenaar, located in the dunes near the governmental residence in The Hague, is the second richest municipality of the Netherlands. The average income is some 65% higher than the national average, and much like in many of the other wealthiest municipalities, the VVD traditionally tops the vote here. The last time it did not come out on top was in 1962, and the party still received 52% of the vote in 2002. But the effects of a long-running local sex and financial scandal and serial defections from the VVD took their toll, and this time it received just 20% of the vote, down from 37% four years ago. However, in other wealthy municipalities like Bloemendaal, Blaricum, Naarden and Heemstede the party lost no more, proportionally, than it did overall, leaving it with some 22-30% of the vote – only in the country’s fifth richest municipality, Laren, did it lose considerably more. In Heemstede, however, its losses did mean that the VVD didn’t come out on top for the first time in at least fourty years.

The party did best of all on the island of Vlieland (43%), the second-smallest municipality in the Netherlands by population, and the traditional right-wing bulwark of Rucphen, in the southwest (38%). Rucphen is a very different town from the Wassenaars and Bloemendaals of the country, marked by turnout rates as low as those in the wealthy villages are high. The municipality includes the bricklayers’ and carpenters’ village of Sint Willebrord, back in the fifties the poorest village of the Netherlands, which votes disproportionally for far-right populists whenever those are on the ballot – a trend which persisted even through the relative lack of such parties in postwar Dutch politics. Thus, the briefly successful Farmers Party received 21% of the vote in Rucphen in the national elections of 1967 (versus 5% nationally); the misleadingly named Centre Democrats received 9% here in 1994 (compared to 2% nationally), and the LPF received 31% of the vote here in 2002 (17% nationally).

In 2010, the PVV got its best result in the country in Rucphen; its tally in the Sint Willebrord precincts reached 55% of the vote, leading a local newspaper to rename the village “Sint Wildersbrord”. The PVV also remained the largest party in 2012, despite losing a third of its national vote. In short, don’t expect the VVD to do as well here in the European elections, when the PVV is taking part.

Some relief for the Christian-Democrats and the Green Left

The Christian-Democrats (CDA), which have been in decline for a very long time and received just 8.5% in the 2012 national elections, have traditionally been relatively strong in local elections, in part thanks to the lower turnout (Christian-Democratic voters tend to be older and more rural, and turn out more reliably than most), and in part thanks to persisting local loyalties and traditions. Thus, in 2010 the CDA received a higher share of the vote (15%) in the local elections than in the national elections (14%), despite local parties taking a sizable chunk of the vote in the former.

The first prognoses on election night this year, however, painted a gloomy picture for the party: it would lose well more than a quarter of its vote. The prognoses were wrong. In the end, the CDA lost less than half a percentage point and only some 30 of its 1530 council seats. Sure, that was still its worst result in local elections since the party was founded in the 1970s, but it also left it easily the largest single party in municipal politics, and the party leader Sybrand Buma was elated. “We have found the way back up again,” he claimed, “we have shown that we can beat the polls and prognoses”. The party’s best result came in the deeply catholic town of Tubbergen, in the east, where it received 51% of the vote. That’s down from 71% in 2002, however.

There was also a measure of relief for the Green Left, founded in 1990 as a merger of radical, pacifist socialist, communist and left-wing evangelical parties. The new party had a rough start in the early 1990s, losing over a quarter of its members by estranging some of the radical-left supporters of its forebears, while failing to achieve a cross-over appeal to a wider left-wing electorate, but it fared well under the leadership of Paul Rosenmoller in the late 1990s. In the national elections of 1998 it got over 7% of the vote, and the party attracted a lot of new members when it profiled itself as the most assertive critic of the new, Fortuynist far right.

Under Rosenmoller’s successor, Femke Halsema, the party completed its transformation from a chaotic left-radical coalition of protest groups into an electorally successful party of the postmaterialist, cultural left. However, despite being personally popular, Halsema oversaw a gradual erosion of the party’s standing, as it lost four of its 11 MPs, 2 of its 4 MEPs and 46 of its 77 provincial deputies. She still led the party to a partial recovery in the 2010 elections, but her succession was clumsily arranged, resented by the party’s left, and turned into a PR disaster when the party board tried to deny a young Moroccan-Dutch member the chance to challenge anointed successor Jolande Sap.

Throughout 2012 (as I recounted in a comment at the time), the party seemed more intent on ripping itself apart with backbiting, leaked criticisms and embarrassing revelations (such as that the party board had tried to oblige aspiring Halsema successors to take an IQ test) than waging an election campaign. Moreover, its embrace of the 2012 “Spring Accord”, alongside D66, the Christian Union and the right-wing government at the time, received plaudits from the media commentariat but teed off the other left-wing parties.

After years of Halsema steering the party toward a more social-liberal course, the party’s participation in an agreement with the country’s center-right parties – as well as its accompanying rhetorics about being the more innovative, reform-minded and responsible alternative to Labour and the Socialists – seemed to have pushed it to a position somewhere to the right of Labour. Such a strategy might have worked for the German Greens under Joschka Fischer, but the problem was: the Netherlands already had a center-left, pragmatic party for the university-educated upper middle class. It’s called D66. So, sure, the Green Left had proven itself a pragmatic, governance-oriented group of political professionals. But it now lacked political coherence, a natural electorate, political allies, an engaged and enthusiastic membership, and ties to social movements outside parliament – and they didn’t even seem to like each other. So what was the Green Left for?

The 2012 election results were correspondingly devastating: the Green Left received 2.3% of the vote and 4 seats (and that fourth one only thanks to a technical alliance with the Labour Party). The Green Left suddenly was barely larger than the Party for the Animals (1.9%). There were calls for the party to just abolish itself, and Sap was forced out, amidst more psychodrama, against her will. She was replaced by Bram van Ojik, a rather bland, but principled old-timer who’d still been active in one of the party’s predecessors, back in the eighties. Since then, the party seems to have tried to keep a low profile, work diligently in parliament, and at least somewhat return to its roots.

Since the Green Left still had well over 400 local councillors, having held its ground well in the 2006 and 2010 municipal elections, a lot was at stake for the party in these elections. And on election night, it could breathe a sigh of relief: it had not done well, but not horrendously either. It received 5.4% of the vote, down from 6.7% in 2010. It kept 354 of its seats. In Utrecht, the country’s fourth-largest city, it was no longer the largest party, but placing second-best with 17% of the vote isn’t bad either, and its place in city government remains ensured. It’s the same story in Nijmegen, where it got 18% after losing less than a percentage point. Its place in city government is also already assured in cities like Maastricht, Breda and Apeldoorn.

In Amsterdam the party lost some 4% but still has over 10% left. In its traditional bulwark Wageningen, the seat of a small university famous for its agricultural science studies, the party remained in second place with 18% of the vote and less than a percentage point loss. It even made some gains, mostly in the countryside and smaller cities; in Roermond it doubled its score to 12%. The party’s top results this year included some unusual places: topped by Oostzaan, near Amsterdam (22%), the list includes rural municipalities like Zuidhorn (20%), De Marne (20%), Wormerland (20%) en Gulpen-Wittem (19%) and the upscale Naarden (20%) before Nijmegen, Wageningen and Utrecht. That’s an altogether different numeric universe from the top results of the Party for the Animals (6% in Vlagtwedde and in Buren). The party also still has a fairly healthy number of members.

The Dutch Bible Belt, and its ambiguous relationship with Islam and Geert Wilders

The smaller christian parties, the Christian Union and the SGP, tend to have an even greater relative advantage in low-turnout elections: their voters are the most faithful of all. It was no different this year. While the two of them together pooled 5.2% in the last national elections, they received 7.3% of the vote in these local elections, marginally up from the 6.6% they got the last time round. And because their vote is concentrated in small, rural municipalities, their share of council seats is even higher: 671 of them, or close to 8% of the lot, which is significantly more than the SP’s number of seats (440) and not much less than the Labour Party’s (799).

Both parties serve strictly protestant electorates, and have their roots in historical (and to me, fairly obscure) religious schisms among Dutch protestants and calvinists. The acronym SGP stands for State Reformed Party (founded 1918), while the Christian Union is a merger of the Reformed Political Union (founded 1948) and the Reformed Political Federation (founded 1975). The SGP especially has an extremely stable, and rather isolated electorate: ever since 1925, the party’s consistently got between 1.6% and 2.5% of the vote in national elections, without exception getting either 2 or 3 seats. Together these three parties used to be known as “the small right”.

Nowadays the Christian Union has a fairly big-tent, evangelical approach to religion, however. Moreover, while it retains its principled opposition to abortion, gay marriage, euthaniasia and other such erstwhile hot-button issues, it steers a centrist or even center-left political course on non-religious issues. It has even gained respect on the left with its opposition to Wilders’ xenophobia, its defense of international development aid, its support of refugees and asylum-seekers, its stress on environmental protection and its socio-economic policy preferences.

On the other hand, the SGP has kept up a more dogmatic political line, and on some issues has only been dragged into modernity by force. Its political program explicitly calls for theocracy as end goal. The party only started actively engaging with TV and radio in the 21st century. Its website content is not available on Sundays. Most notoriously, the party only allowed women to become party members in 2006, and only made it possible for women to run for office on SGP lists last year – and both changes only took place under judicial pressure, from both Dutch courts and the European Court of Human Rights.

Both parties, however, still overwhelmingly pull their votes from the Dutch Bible Belt – yes, the Netherlands has a Bible Belt – which snakes through the countryside from parts of the watery southwestern province of Zeeland to places like Rijssen and Staphorst in the east. They also often run common lists, especially in municipalities where they are too weak to otherwise stand much of a chance to win seats. Where they are strong, however, they are very strong. In Staphorst, the SGP received 31% of the vote and the Christian Union another 24% – leaving an additional 26% for the ‘mainstream’ Christian-Democrats and just 19% for all the secular parties together. In the fishing village of Urk, the SGP took over from the Christian Union as largest party, 25% to 24 – apparently, the local Christian Union’s relatively liberal positions (they’re OK with letting the buses run on Sundays, letting shops open on Boxing Day, and tolerating alcohol use for 16 year olds) were not appreciated. Before the rise of a local party called Heart for Urk, moreover, back in 2006, the two parties were still pooling 67% of the vote here, with another 20% for the Christian-Democrats.

But it’s not just in folkloric, staunchly Calvinist villages that the parties did well. In Zwolle (pop. 123,000), the Christian Union became the largest party, gaining 5 percentage points to get 19% of the vote, ahead of Labour and D66. In Ede (pop. 111,000), the SGP became the largest party by holding more or less steady at 16% of the vote.

There was a historic occasion too: in the wake of the SGP’s acknowledgement last year that it had to allow women to run for office, the first female SGP councillor ever was elected, in the southwestern town of Vlissingen where the party had not been represented in the council before. Lilian Janse was accepted as lead candidate by the local party after six different men had passed on the offer. A “dream becomes reality,” she said.

One issue that somewhat divides the two small christian parties is Geert Wilders’ trenchant criticism of Islam. Unlike Wilders, both parties defend the right of Muslim women to wear a headscarf (for obvious reasons, perhaps, considering the traditional dress in their own bulwarks). When Wilders declared that the Quran should be banned, the Christian Union denounced it as a breach of the freedom of religion, while SGP leader Van der Staaij rejected a ban as well (commenting that “even in Calvin’s Geneva it was not on the list of forbidden books”), but couched his opposition in warnings against the “islamisation of the Netherlands”.

Former Christian Union leader Andre Rouvoet, in particular, used to sharply criticize Wilders. He called his appeals to judeo-christian traditions “opportunistic,” emphasizing that those traditions also instilled values such as “love of one’s neighbour and defending minorities” and warning Wilders “not to interpret them selectively”. He accused Wilders of attacking the rule of law: the fundamental freedoms of religion and education apply equally to all, he insisted, and could “only be brushed aside for muslims by abolishing them altogether”. Any violation of that principle is “unacceptable in a democratic state of law, unacceptable!”, he exclaimed, as defending everyone’s freedom is “essential” to Christian politics. The SGP, on the other hand, does not believe in freedom of religion in the first place, only in “freedom of conscience”; in line with Article 36 of the so-called Belgic Confession, the party’s program argues that “false religions and anti-christian ideologies should be kept out of public life by the government”.

The difference between the two small protestant parties was confirmed in a poll by a Dutch Reformed newspaper. Almost 15% of SGP voters “often” or “almost always” agreed with Wilders, the 2007 poll found, versus just 5% of Christian Union voters. 20% of SGP voters, and only 4% of Christian Union voters, agreed with his proposal to ban the Quran. (Remarkably, the proposal found little more support among the PVV’s own voters – just 23%; perhaps a sign that even his own supporters recognize that much of what Wilders says is political theatre).

That diffference has diminished over time, however. In his remarks, Rouvoet already seemed aware that not everyone in his electorate was as vigilant as he, expressing surprise about the “naivity” with which orthodox protestants sometimes approach the PVV; and indeed, party members were to adopt a resolution at the party’s annual congress in 2011 that called on the party to treat the PVV like any other party it disagrees with, and to approach the government at the time, whose reliance on PVV support the party’s leaders had sharply attacked, constructively. The party’s tone does seem to have changed since. Christian Union Senator Roel Kuiper called for including a ban on Sharia law in the Dutch constitution earlier that year, and in 2012 one of the party’s current MPs, Gert-Jan Segers, said: “I’m not going to stay silent out of fear to be grouped with Wilders. He brings up an important theme”. (Drawing a precarious line, he also said that muslim religion teachers should not be allowed to teach children that “you can stone gays” but, pressed by the interviewer, argued that teaching kids that gays will burn in hell, as is done on orthodox-christian schools, is part of “the freedom of education”.)

All of which is not far removed from what SGP Senator Gerrit Holdijk said in 2009, in a remark which also hints at why christian politicians in the highly secular Netherlands had been loathe to denounce Islam in the first place: “I think Wilders is fulfilling a very useful function at this moment [..]. He is raising issues about immigration and integration which others had left untouched for years. The SGP too has always been very reticent to explicitly mention problems around muslims, mostly because they thought: “If muslims are tackled, we’ll be next”.” Which did not stop him from proposing that Whit Monday could be replaced as national holiday by Eid al-Fitr.

A final observation about these two small parties: that 2007 poll also showed that 61% of SGP voters would opt for the Christian Union if their own party did not take part, but the feeling is not mutual; only 13% of Christian Union voters would opt for the SGP if their party did not take part. Instead, 44% would opt for the Christian-Democrats.

Two cities with a muslim party, and other local news

All this talk of bible belts and Geert Wilders should provide a good excuse for a different observation: Rotterdam becomes the second Dutch city to see an expressly muslim party win council seats. The new party, NIDA, won 5% of the vote and two seats. Efforts to establish specific parties for people from immigrant backgrounds, whether under a muslim, specific ethnic or generic “minorities” banner, were very long as unsuccessful in the Netherlands as elsewhere in Western Europe – or as efforts by Romani parties in Eastern Europe, for that matter. Ethnically Turkish, Moroccan or Surinamese voters in the Netherlands tended to faithfully vote for the Labour Party. But this culturally very diverse electorate has started spreading its votes more widely in the last two decades, with the Green Left, the Christian-Democrats, and later on even the VVD and the far right making some inroads. The local elections in 2006 marked the first time that a specifically Muslim party won a council seat: the IslamDemocrats won a seat in The Hague. The phenomenon was there to stay: this year, the IslamDemocrats received 4% of the vote and gained a second seat in The Hague, while an additional party basing itself “on norms and values in Islam”, the Party of Unity, kept the council seat its leader has occupied there since 2006, getting 3% of the vote.

A student party gained a first seat on the Utrecht council. They have much to learn from their peers in Delft, where there is a large technical university; STIP (which originally stood for “Technical Students in Politics”), has been on the council there since 1994, and this year became the town’s second largest party, getting 11.4% of the vote. If that sounds like the vote in Delft must have been very fragmented, that’s exactly right – but it can be worse. In Vlaardingen, a suburb of Rotterdam, the Socialists became the largest party with just 14% of the vote, against 13% for Livable Vlaardingen, 11% for the Labour Party, and a total of eleven parties on the council.

While Livable Rotterdam and, apparently, Livable Vlaardingen are flourishing, the List Pim Fortuyn (LPF) brand is all but history. The only local party with council seats still bearing that name, in Eindhoven, lost one of its two seats. One of the LPF’s government ministers in what ended up the shortest-lived government in Dutch history (2002-2003), however, is riding high. Hilbrand Nawijn may have added a generous helping to the freakshow the LPF became after Fortuyn’s death, his List Nawijn just became the second-biggest party in Zoetermeer (pop. 124,000) with 15% of the vote.

There was also some exciting local politics in Rijswijk (pop. 48,000). The local party Independent Rijswijk, which surged into a dominant position in municipal politics in the early ’90s, imploded over a conflict between alderman Dick Jense and local councillor Ed Braam, who founded his own party (“Better for Rijswijk”). Take it away, Dick Jense: “I also don’t know where this idea comes from that I consider Ed Braam untrustworthy. I did indicate in a private chat on Facebook that I would never take part in a local government with Braam’s party, because he can’t be trusted.” Got that? The conflict had consequences: Independent Rijswijk saw its vote drop from 21% to 9%, whereas Braam’s new party (with a candidate list that included Jense’s sister) received 16% of the vote. He’s a big Wilders fan, by the way, who has boasted that “Geert had no objections against me calling my party a PVV clone”.

In Moerdijk, meanwhile, 44% of voters cast a blank ballot in protest against what locals consider official neglect of the village, which is being squeezed by a large industrial harbour.

Communists! Actual communists! Alive! United (of sorts)!

There are a couple of municipalities in the Netherlands where local leftwing parties exist alongside (or rather: to the left of) the Socialists, the Green Left and Labour. There is ROSA in the former industrial powerhouse of Zaanstad (pop. 151,000), which was founded in the mid-90s and increased its vote from 4% to 7% this year, its best result yet; and there is Roodgewoon (which could be translated as “Simply Red,” but without Mick Hucknall connotations) in Hoogezand-Sappemeer (pop. 34,000), which first took part in 2002 and this year received 10.3% of the vote, also a new high. An attempt by a former Green Left member in Nijmegen to resuscitate the brand of the erstwhile Pacifist Socialists (PSP) failed however, with just 0.3% of the vote.

There are also, however, a few genuine, actual communists left. What’s more, apparently, if on a highly local scale, they’re sort of thriving.

To go on a brief historic detour: the Communist Party was never as strong in the Netherlands as in many other continental European parties, but right after the Second World War it did pull 10.6% of the vote in the first postwar national elections. The Cold War and the party’s support for the suppression of the 1956 revolution in Hungary pushed the communists into political isolation, however. A bitter internal purge of prominent communists and WW2 resistance heroes who had dared insist on a change in course after Stalin’s death (and were summarily smeared as really having been “British spies” in the war), didn’t help. By 1959, the Communist Party (CPN) received just 2.4% of the vote. However, the party retained a loyal core of support in and around Amsterdam, especially among dock, steel, and railway workers, as well as in the rural northeast of the country. In the east of the province of Groningen, a history of “Lord-farmers” operating latifundia-like farming had created a class of landless peasants who later found work in strawboard factories, before those folded too, and they retained a strongly proletarian ethos and often corresponding communist sympathies. (There’s a great TV documentary, in Dutch alas, explaining all this, called Lenin in Finsterwolde.)

Up through the fifties and even the late sixties and early seventies, the party kept getting 15-20% of the vote in the various municipalities that would later merge into Zaanstad and nearby municipalities north of Amsterdam, like Oostzaan, Ilpendam and Landsmeer. In Amsterdam itself it remained the second or third largest party until 1974, and it remained part of the city government up through the mid-80s. Across the country the party experienced something of a revival in the early 1970s, getting 4.5% of the vote in the 1972 elections (including 10% in the province of North-Holland and 9% in the province of Groningen), and its membership crept back up from around 10 thousand to over 15 thousand in 1980. The large influx of New Left-type intellectuals was to spark attempts to modernize the party into a more feminist, environmentalist, movement-like organization, however, which alienated most of its old base of industrial workers. The Labour Party’s pull under Den Uyl, which got its best result ever in 1977 (34%) did the rest: the CPN dropped to 2% of the vote for a while, and in the 1986 elections it lost all its MPs when it received just 0.6% of the national vote. Soon after, the party abolished itself and merged into the Green Left.

Much of those developments, however, passed by the party’s bulwarks in the far northeast – and if this sounds like the beginning of an Asterix and Obelix story, thats because it’s a bit like that. In Finsterwolde, the party kept getting an absolute majority of the votes even in national elections until 1977, and barely less than that in 1981 and 1982. In Beerta, its share of the vote dropped merely from 49% in 1971 to 39% in 1982. In places like these, the merger into Green Left met little in the way of support and understanding; even the CPN’s only-ever mayor, Hanneke Jagersma in Beerta, resisted. A new party, the VCN, was quickly formed, soon renamed into the New Communist Party (NCPN). The NCPN failed to make any traction whatsoever in national elections, getting all of 0.1% of the vote in national elections in 1994, 1998 and 2003, and even at a provincial level never surpassed 1.4% (Groningen, 1999). But it kept dominating in local elections in the far northeast for a while, until it was undone by internal divisions and, eventually, a municipal merger.

When Beerta and Finsterwolde merged with Nieuweschans into Reiderland in 1990, the communists still survived, with the NCPN getting no less than 50% of the local elections vote in 1994. In 1998 that number dropped to 36%, but it stabilized in 2002 (34%), leaving the party once again the local #1. The party suffered something of an embarrassment in the national elections that year, however. Considering its previous lack of success, the NCPN had deemed it better to save some money and not take part in those; but then Pim Fortuyn happened and Reiderland promptly yielded the best result for his new party in the entire north. And at the very least, the results strongly suggested that the NCPN voters had in fact bolted straight to the far right. Further embarrassments followed: when the party took part in the national elections again in 2003, it received just 8% of the vote in Reiderland, and in the municipal elections of 2006 the NCPN’s share of the vote was halved to 18%. A lot of that had to do with a fierce local debate about a project called “the Blue City,” which involved building a new settlement by the lake of highly priced luxury housing. Comrades in neighbouring Scheemda deemed the NCPN to not have resisted the project properly and founded their own party, grandly naming it the United Communist Party, which supplanted the NCPN there and got 10-14% of the vote in 2002-2006.On top of all of that, provincial authorities were pushing through another municipal reorganization, and after just twenty years of existence, Reiderland was merged with Scheemda and the much larger Winschoten into the new municipality of Oldambt (pop. 39,000). And that seemed the end of that; after all, the aggregated result of the two communist parties in Reiderland and Scheemda in 2006 would have amounted to just 7.1% of the vote in the new, larger municipality, and it would be evenly divided into two equally small shares. But it wasn’t quite the end. First, in the 2009 local elections, the United Communists succeeded largely in coalescing the party vote, getting 8.5% against the NCPN’s pitiful 2.3%. And now, this year, the United Communists have actually doubled their numbber of seats to four, and increased their vote share to 15.8%. That has made it the second-largest party in the municipality. The largest? Why, the Socialist Party of course, which should surely make this municipality the most leftist of the country.

Moreover, this year the United Communists also took part in neighbouring Pekela (pop. 13,000), and gained a there seat as well, almost starting to justify their party name. And that’s not all either; the NCPN won a second seat in Heiloo, in the province of North Holland (pop. 23,000), upping its share of the vote there from 7% to 10%. And unlike eight years ago, when the party had also already gained a second seat in the elections but had to leave it empty because, well, its list only had one candidate, this time a second communist was at hand to take the new seat. The party leader there, Willem Gomes, is quite the character, by the way. A couple of years ago, he paid for an advertisement in the local newspaper in which he published all the salaries and end-of-year bonuses of the local politicians. They were not pleased.

There is one more town where communists have kept seats in the local council after the CPN’s dissolution: in Lemsterland the NCPN had 2-3 seats on the council from 1994 until the municipality was merged into De Friese Meren last year. There’s an interesting documentary about that too: Lenin op ‘e Lemmer (because apparently these things all have to have basically the same title). In the council of the new, larger municipality there is still one communist – so maybe the way back up should continue there.

First, however, the comrades in the northeast face yet another round of municipal reorganization, as the province of Groningen has embarked on a drastic reduction of the number of municipalities to just six. Moreover, whereas newly merged municipalities in the north and west of the province will be allowed to remain at some 50-60,000 inhabitants, the east of the province is supposed to merge into two much larger units of about 100,000 inhabitants each, which really is disproportionally large for Dutch municipalities. All of this less than ten years after Oldambt was created. Since the new mergers will undoubtedly again marginalize the remaining communists – of the four communist councillors in Oldambt now, I would guess that just one would likely survive – one could imagine some communists feeling a little paranoid, especially against a historical background in which the national government removed the powers of local councils and mayors in Finsterwolde and Beerta at time when those became too communist. That was long ago, though, during the Cold War, and the communists are a mere shadow of what they once were – we’re talking about a pooled vote of about 5,000 in Oldambt, Pekela and Heiloo together. (In comparison, Rosa and Roodgewoon added up to some 5,500 votes, while the Pirate Party this year received some eight thousand votes in total in the various municipalities it ran in, or about 0.12% of the national vote.) Presumably the provincial bureaucrats nowadays have more important matters in mind.

Either way, the upcoming merger seems inevitable; although all its opponents (socialists, communists and Oldambt Aktief) gained votes in Oldambt, they still don’t have a majority on the council, and the outgoing council has already hastily voted in favour of reorganization right before the elections. The only question left to settle is about which municipalities in East-Groningen should merge with which other ones. A provincial commission had suggested to merge Oldambt with Stadskanaal, Vlagtwedde and Bellingwedde. This would be bad for the communists, as Stadskanaal is less left-wing than most municipalities in the region. Moreover, Stadskanaal is OK with the idea, but the councils of Vlagtwedde and Bellingwedde are OK with merging with each other, but not Stadskanaal (are you still following this?).

Instead, the Oldambt council voted for an alternative merger with Hoogezand-Sappemeer, Slochteren and Menterwolde. Hoogezand-Sappemeer agrees. In this model, the current Oldambt would constitute about 38% of the new municipality’s population. It’s still bad news for the communists, since none of these other three municipalities have a communist tradition. Either way, a new municipality would mean new elections, and perhaps a new blog post here.