Today, the folks at First Read write:

Today, the folks at First Read write:

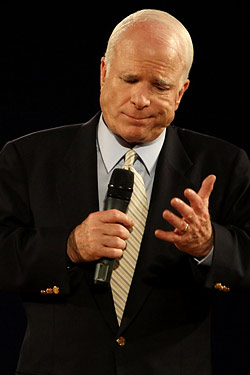

*** The Colin Powell floodgates: Three semi-notable Republicans came out for Obama yesterday, including two former very-moderate Republican governors: Arne Carlson of Minnesota and Bill Weld of Massachusetts. Neither is that surprising to those that know the politics of the two ex-governors, but to a layman’s eyes, it’s not good news for McCain. What is striking here is that these endorsements underscore how McCain somehow lost his moderate identity — even among Republicans who seem to know him well. Seriously, these are the type of Republicans the McCain of 2000 would have counted on as his base. How did McCain end up being the nominee that was overly focused on wooing the base? How did he lose this middle-of-the-road mojo? Forget the Bush issue and the economy; McCain’s inability to keep his moderate identity might be the biggest mistake bungle of the campaign.

I agree that this is a central problem with the McCain campaign. McCain got the nomination in part because he was able to convince two very different groups — the religious conservatives and the moderates — that he was their guy. The moderates had loved him since 2000, and were happy to finally have a chance to brush past the Bush machine and get McCain elected. The religious conservatives were skeptical but they didn’t have that many options — there was a deep distrust of the Mormon Mitt Romney, and Mike Huckabee didn’t seem to be a serious contender (though I think it’s significant that he received as many votes as he did). Divorced, cross-dressing, gay-friendly Rudolph Giuliani of New York City was an even worse choice for this group than McCain.

So they were brought along, grudgingly. And the grudge showed. McCain faced a daunting enthusiasm gap — Obama supporters were far more passionate about their candidate than McCain’s supporters were about theirs. And all of the basics that come from a fired-up religious conservative base were imperiled — the people who were so instrumental in giving George W. Bush the presidency in 2000 and 2004 threatened to do only half-hearted work for McCain or, worse yet, just stay home.

Then came Sarah Palin.

More and more evidence has emerged that she was a startlingly late and hasty pick, made when McCain advisors put the kibosh on the person McCain preferred, Joe Lieberman. An explicit reason given was that Lieberman would alienate the base, while Palin would bring them home. And that was the choice McCain made — go with the moderates or go with the religious conservatives?

He went with the religious conservatives. This seemed to be a good decision for a while, but then more and more of the moderates started stepping off the bus. McCain had been trying to hold on to both constituencies with winks and nods, but just as the Palin choice reassured the religious conservative base that he really was allying himself with them, it had an equal and opposite reaction amongst the moderates. Some of them were instantly appalled, some of them took a while to come around. But I think the Palin choice, more than anything else, crystallized which group McCain found more important — and the other group wasn’t happy.

The choice not only showed his priorities but undermined some of the very qualities that made him most attractive to the moderate group — his supposed strength of principle, the whole maverick persona, the guy who would denounce the agents of intolerance. If he seemed to contradict such a bedrock principle for the sake of winning the election, what else would he compromise? Was he the person they supported, the person they thought they knew?

The answer seemed to be “no.” Andrew Sullivan, for example, was moved to write a post called “Scales. Eyes. McCain.”

McCain’s suspension of his campaign to magically solve the financial crisis reinforced the problems shown in the pick of Palin — an emphasis on gimmickry rather than on governing, on electioneering rather than seriousness. And of course it didn’t help that the gimmick was spectacularly ineffective.

But I think that the Palin pick was the signal moment, the moment that a choice between the two disparate groups was made. I’m not sure the opposite choice would have been the right one, though. I’m not sure if McCain could have done that much better if the base had stayed apathetic and the moderates remained enthusiastic. It was a paradox inherent in McCain’s candidacy — these two groups each demanded a show of allegiance, and once he moved past winks and nods, one of those groups was going to be disappointed.