This post was originally published in April 2009 on a blog that’s now dead, where it’s no longer online. Turns out I still had a draft saved here, so I thought I might as well republish it.

Or: a collection found on the street tells the story of minor apparatchiks in love.

Once every couple of months it’s big garbage day in my district. This means everyone takes out all the shit they don’t want anymore and dumps it on the sidewalk. It’s like Queen’s Day in Holland, except nobody’s selling anything. Mounds of stuff, discarded sofas, broken cupboards, old books, soiled shirts, cardboard boxes and piles of random garbage heaped onto the pavement in clusters.

This means lots of activity. Early in the morning the diggers trek into the neighbourhood. Elderly people, Roma. Stuff gets carted into car trunks, folded into plastic bags. Trabants with trailers that are stacked full take off to the suburbs.

In Holland you had rag and bone men until the sixties or so I think, who would come by to collect stuff that’s nowadays hauled off by the municipality’s “big trash” service on request. This is like that – just on a really large scale. Mostly it just means a lot of trash you have to circumnavigate when you walk down the street, but at its best, or worst, it has a near-Third World feel. A bony old man pulls a makeshift platform on wheels with cardboard stacked up a meter high down a busy road, passing cars swerving around him.

One of those days, a couple of months ago, we took a walk and rummaged through the piles out of curiosity. Found some dumpy Hungarian textbooks, a couple of novels in seventies covers. And photos. Not once, but twice, we found photos. One pile of photos sprawled over the pavement in Nyár utca, dirtied by shoes, some still shoved into a box along with other papers; postcards too, Christmas cards, holiday greetings from Slovakia. The other, larger pile at the beginning of Dohany Street, across from the synagogue, in a box in between newspapers, random stuff.

Budapest and Dunaújváros

I’ve dubbed the first collection “The apparatchik”. These photos belonged to a couple called Lajos and Zsuzsa Dömötör (I googled them, but found no leads). I assumed at first that Lajos had been a minor official, back under the old regime – but going through the photos and translating the texts of postcards with the help of fellow Flickr members (in particular GCsanadi), it turns out that it was Zsuzsa who must have been the apparatchik. Unfolding the story locked into these photos and postcards turned out to be fascinating – if like me, you’re the kind of person who finds fragments from the past’s quotidian life the most interesting thing.

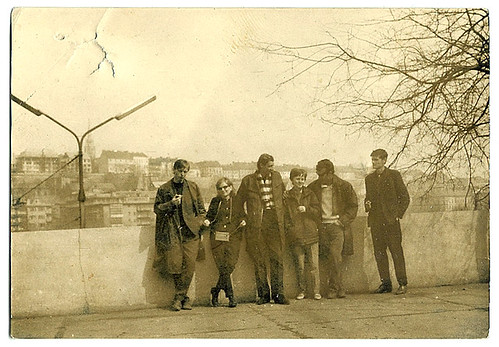

The oldest photo in the set shows a group of young men and women at the shore of the Danube, in Budapest. Students? Were the Dömötörs among them, unmarried yet? Or just one of them? Handwritten on the back: March 1967, Budapest. On the left, in the background, is the Matthias Church on the Castle Hill – unframed, still, by the mirrorring windows of the Hilton hotel that was built right next to it later.

Whether one, or both of them were just visiting Budapest when this photo was taken or living there as a student, their hometown, once they were married, would soon be Dunaújváros. They lived there for a long time – judging on the postmarks, at least until 1984.

Dunaujvaros is a mid-sized industrial town some 35 miles south of Budapest, but not your typical one. It was built from scratch in the 1950s as a communist model city of sorts – except back then, it was called Sztálinváros, “Stalin City”. It had the country’s largest iron and steel works. Foreign visitors like Yuri Gagarin and President Sukarno were proudly shown around the town. By 1980, the city had some 60,000 inhabitants. But the collapse of heavy industry in the postcommunist era hit the town hard and now there are fewer than 50,000 left.

The apparatchik

What did the Dömötörs do there? Lajos, as this photo illustrates, appears to have been something official. Maybe he, too, was a minor apparatchik. Maybe he was just a teacher, or a supervisor in a factory. One of the two was a photo enthusiast: some of these photos were home-developed, and printed back to back on photopaper. Think small: this one’s less than 9×6 cm…

We do know a little more about Zsuzsa’s work, as she sent hom this postcard to her man:

Looks exciting, doesn’t it? “Dear baby,” she wrote (literally: “my little one”), “Many kisses from Balatonaliga, [from] the holiday home of the MSzMP KB.” Balatonliga is a small town on the Balaton lake, presumably one of the many lakeside resorts there (trivia: it’s got a building complex named after Gagarin right in the centre). The MSzMP was the Hungarian Socialist Workers Party, or the ruling party in communist Hungary.

The KB was the party’s Central Committee. That sounds impressive, but need not be, GCsanadi explained: “This is the not-so-elegant part of the resort center of the Central Commitee – wich was the wider elected body and the bureaucratic organization of the ruling Party. (The more important, smaller center of power was the Political Committee, sometimes called Politburo).”

In short, Zsuzsa could have been “some kind of secretary or lower status administrator within the office of the Central Committee”. On the postcard, she continued, somewhat tantalizingly: “Be very well my dear, and look after yourself. The holiday home is wonderfully beautiful and has all conveniences. I’m a very good little girl, my sweet, you also be good. So long, lots of kisses. Zsuzsa”.

A darling bonus is the ballpointed cross drawn on the second room from the left on the middle floor, and the scrawl that’s added on the side of the back of the postcard: “x this is the room I’m in!”. Remember doing that as a kid? :-)

Life under goulash-communism

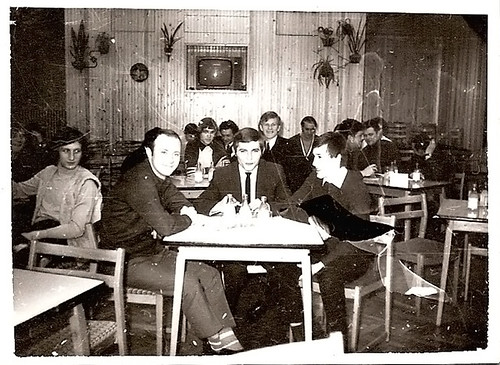

Lajos, in his turn, is featured in quintessentially goulash-communism settings. Is this some kind of canteen or leisure room, or some party resort again? Said Flickr user Anna Kiss: “I remember that style! The wooden paneling and those plants they used to stick on the walls. It was the same in every building you went to in Hungary at that time!”

The Dömötörs were quite progressive, it seems. This photo reminds me to no end of my mom and her leftist, feminist friends in the late seventies … The typical “office plant” in the corner, such a staple in the government buildings my parents worked in back then too, certainly seems to date the scene. Commenter GCsanadi played photo detective:

I think, the photo is taken in an office resort house – maybe a KISz- Iskola (Training center of the youth organisation of the Communist Party). The two parts of the floor (carpet and plastic-linoleum, (if we have such an English word) was characteristic of such public places. Also, the position of the heating is something used in a building where they had a windowed balcony on the right. The telephone is situated in a special place here. The glass is from a canteen, etc.

By that time, the couple had at least one child, too, as this photo illustrates:

What are we looking at? Hungarian commenters again help out. “I have a picture of me and my mum from 1979 just like this,” writes Anna Kiss; “it’s an official registration thing- you sit with another 40 newborn souls, mum gets flowers etc.” GCsanadi provides context: “This event was invented to make some concurrency to the baptism ceremony of the chuch. The name was “névadó ünnepség” (naming-ceremony). The “socialist brigade” organized it, in the registration office, the whole stuff was very characteristic of that period. It was sometimes quite uneasy feeling, as it was not a real spontaneous event, and was a not very successful copy of the religious original. Sometimes the luckiest children got this one – and in secret the religious baptism as well.”

The practice is explained in Jason Wittenberg’s Crucibles of Political Loyalty:

To counter the contact between Church and society associated with religious festivals and traditions, in 1959 the Party introduced a set of civil ceremonies for family events. Christenings [..] were to be replaced with name-giving ceremonies and funerals with farewells, each of which would have a set of rituals associated with them. The idea was to imbue each citizen with the feeling that “from the cradle to the grave his path in life is being attentively followed and sincerely participated in by society, that he is being supported by the comradeship of his fellow workers. He should become used to the idea that our fate is not decided by supernatural powers, but rather by us, through human society, and through the laws of life itself.” These ceremonies gained legal status in 1962 and by 1970 there existed a network of offices to promote civil celebrations.

The communist state made some headway in this competition between church and state over these ceremonial institutions, but not overwhelmingly so. The share of Catholic newborns that were christened declined only at an incremental pace, from 100% in 1951 to 71% in 1984. In that latter year, only 55% of Catholic still had church weddings, but 91% were still demanding Catholic burials.

Greetings from Gelnica

Friends of the Dömötörs, and the Dömötörs themselves, travelled abroad at least occasionally, within the Eastern Bloc. One friend sent a postcard from Krakow, with a rather cryptic text: “I send you my greetings from Poland. After Warsaw and Lodz we are now in Krakow, but here too everything is different from what I expected.” If you let your imagination run wild, you can imagine this to be veiled criticism of the system from a disillusioned communist. Alternatively, perhaps the waiters were just rude and the buildings ramshackle, and that’s what was unexpected.

Another friend sent the above postcard from a skiing holiday in Gelnica, Slovakia. “The snow is scarce, the skislopes are fast”, he wrote. “Still need to practice some. Missing your company. Will try not to break my neck.” Other postcards hail from your typical holiday destinations in Hungary. They received lyrical greetings from friends holidaying on the Balaton: “Dear Timi and Lajkoca, we’re utterly devastated that in such brilliant weather there’s no one to climb fences with! The Spiders are missing out too, because they said it would be a sacrilage to go there without you. Many kisses.”

Nyócker

At some point the Dömötörs moved to Hevesi Gyula utca in the VIIIth district of Budapest. The Eighth is the city’s messy and lively district that natives will warn you against. As one of the city’s poorest districts, it gained almost cult notoriority – as illustrated by the success of the animated movie that took its name from the district’s nickname, Nyócker – even if it is now gentrifying rapidly. Many Roma live there and in the 1990s there was a big problem with street prostitution.

The fact that the Dömötörs landed in the VIIIth suggests that the couple was not in the best financial conditions anymore. Why did they move to Budapest? If they were indeed in their twenties in 1967, they shouldn’t have been up to retirement until just two or three years ago. But Zsuzsa will have lost her job after 1989, and maybe he lost his in the 1990s as well, and they came to Budapest then? Or just a few years ago, after early retirement?

We don’t know when they came. Although the VIIIth was always poor, it only hit on the seriously bad times after the fall of communism. Did the Dömötörs arrive before then, or after? If they were indeed living on pensions, they would have had very scarce resources. The postcommunist transition offered new opportunities for the young, but hit the middle-aged and elderly hard, and pensioners in particular.

But maybe they weren’t in Budapest for long at all, because this is only postcard addressed to their Hevesi utca address – from Greece, no less. A distinctly clunky-looking Greece, though, so maybe it was as far back as the early nineties after all. Maybe they lived in Budapest for quite a while but had just lost most of their social network by then.

After all, the photos did land on the street… There is one final postcard that was sent to an address in Nyar utca, here in the VIIth district, where I found the photos. But it’s addressed to “Ifjú Lajos Dömötör” – Lajos Dömötör the younger. Their son? Was it for him that they moved here? Maybe they actually moved in with him when they moved to Budapest, being scarce of means themselves? But then what happened to him? Why would the photos end up crushed underfoot on the street, in the heaps of garbage?

That part, not even the most keenly observing Flickr commenter can help with. It’s a mystery, and most likely a rather sad and tawdry one. Better to remember the Dömötörs as young, loving couple in the seventies – even if their position did put them distinctly at odds with how many Hungarians experienced the communist era (or did it?).