The holiday season is often used to reflect back on items that are not exactly current news, but worth a re-read over time. This selection is inspired by an off-hand blogger’s comment about Che, but any occasion would have been a good one to dig this one up from the archive.

On a forum, a couple of years ago, I recommended an article by Alvaro Vargas Llosa that was published in TNR in 2005 with these words:

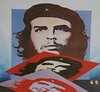

Everyone adores Che as a pop icon.

But the icon means ever less.

For me the following article was an absolute eye-opener.

First, it fillets the visible postmodern reduction of “Che” into what is, in effect, merely an extraordinarily successful market brand. A feel-good product for the young and rebellious. A pre-fab idealistic dream; an instant badge of revolutionary street cred. This part may make you laugh. In recognition; and at the surreality of it.

But then, having wrapped off the countercultural commerce of Che as icon, it also digs into the actual historical record. To recount the rather more sordid story of who “Che” really was. Because filmic sketches of the man’s soul are fine — but what did he mean to those who lived under his actions?

The filmic and biographic portraits of Che seem to almost portray him in a vacuum; an individual soul, a romantic one-man story. But Che held real power. The Cubans and others who had to suffer his idealism are strangely absent in the iconic version of Che. This author puts them back into the spotlight.

This article is very long, and doesnt always make for comfortable reading. But it should be an obligatory read for anyone ever caught wearing a “Che” t-shirt.

Seriously.

Don’t be mistaken about the ironic birds’ eye view of Che-the-icon in the beginning of the article. The rage of the author is real – and very well-informed. It is not that of just another reactionary, either – note the very last section. It is that of one who sees history and fashion reward bloody zealots, and forget those who fought tyrants without killing a fly, and actually achieved results. Because those gentle reformers are so much less glamorous than your failed, bloodthirsty revolutionary.

You can still love the myth if you will. But before you put on the shirt, know about the politics behind it.

The TNR archive is still lost in the site’s technological fail, but the article can be read in full here: The Killing Machine: Che Guevara, from Communist Firebrand to Capitalist Brand.

About Che as icon, by the way — did you know that the famous Che image now adorning the t-shirts of millions of rebellious teenagers came about through a little bit of what we’d now call Photoshopping? To get the “t-shirt Che”, just take the real Che’s photo and make him “slimmer and his face longer, by about one-sixth”.

That was noted in a New Statesman article from 2007, found via the opening post of an instructive thread about Che on the forum Able2Know, Che Guevara … Forty years on.

That thread also features this post on a more serious note: how has Cuba’s death toll under communism compared with that of the brutal Batista dictatorship that preceded it? Not well at all, according to the work of one statistician, R.J. Rummel, who recorded that the Batista regime “killed 1000 of its citizens from 1952 to 1959, for an average rate of 143 per year,” while the Castro regime “killed 73000 of its citizens from 1959 to 1987, for an average rate of 2607 per year”.

According to his data, then, the Castro regime killed at an 18 times faster rate than even the despicable Batista had done, or at a 12.6 times higher proportional rate if you take population growth into account. Admittedly Rummel appears to be a highly controversial figure, so I’d love to hear about alternative estimations, though I can’t imagine an alternative computation would suddenly reverse the roles.